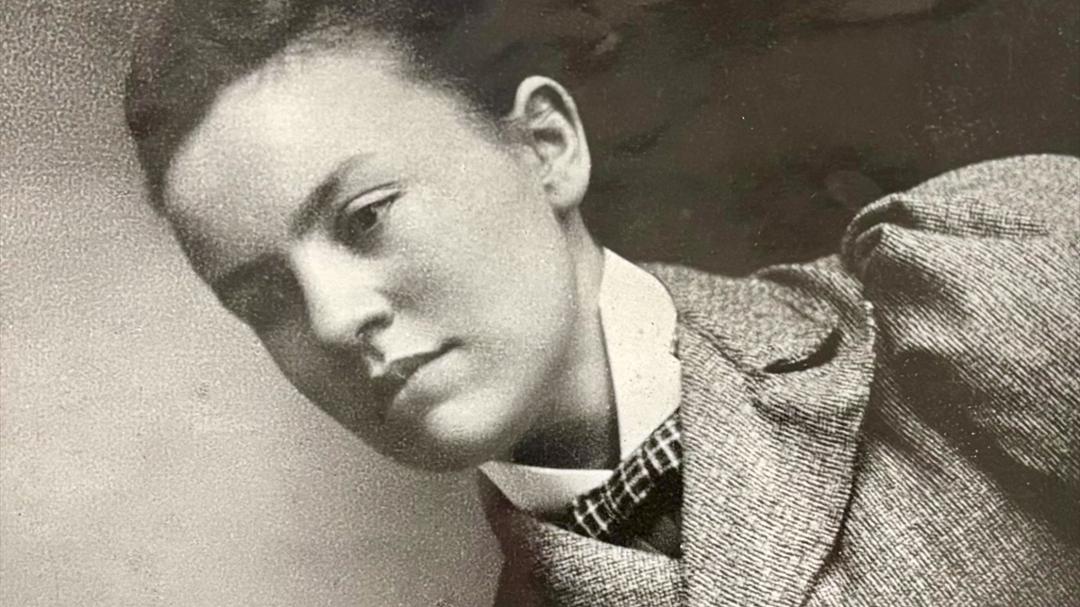

Texas Tech’s first librarian, Elizabeth Howard West, was a force of nature and someone truly ahead of her time.

Photos courtesy of Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library.

Texas Tech University was little more than a few buildings dotted against the vast horizon when Elizabeth Howard West arrived as a pioneer who saw not what the small college was, but all it could become.

She understood that successful universities, like any great venture, are built brick by brick, or in this case, book by book.

The first librarian of the new Texas Technological College was recruited from her position as state librarian in Austin. She was the first woman to head a department in Texas state government.

But like the new West Texas campus, Elizabeth came from humble beginnings and fastidious fortitude.

“Some are pioneers because of the time in which they live; others would be pioneers anytime. Elizabeth Howard West was one of the latter group,” said Goldia Hester in her 1965 thesis on the aforementioned.

The unique steward of Texas Tech’s books inspired theses, awards and invitations to some of the finest creative collectives in the country. But these accolades were met with responses saying something to the effect of, “I regret my delay due to my being very busy and having little clerical help.”

Texas Tech’s first librarian was truly as rare as the books she shelved.

Known for walking campus in a felt hat and cape, Elizabeth, or “Bess” as more intimate acquaintances called her, spent almost 20 years establishing the school’s library. When she arrived, the task before her was a challenge. There were no books, no cataloguing systems in place, and the space allotted could barely hold 10,000 volumes, which may sound like a lot, but left little room for expansion.

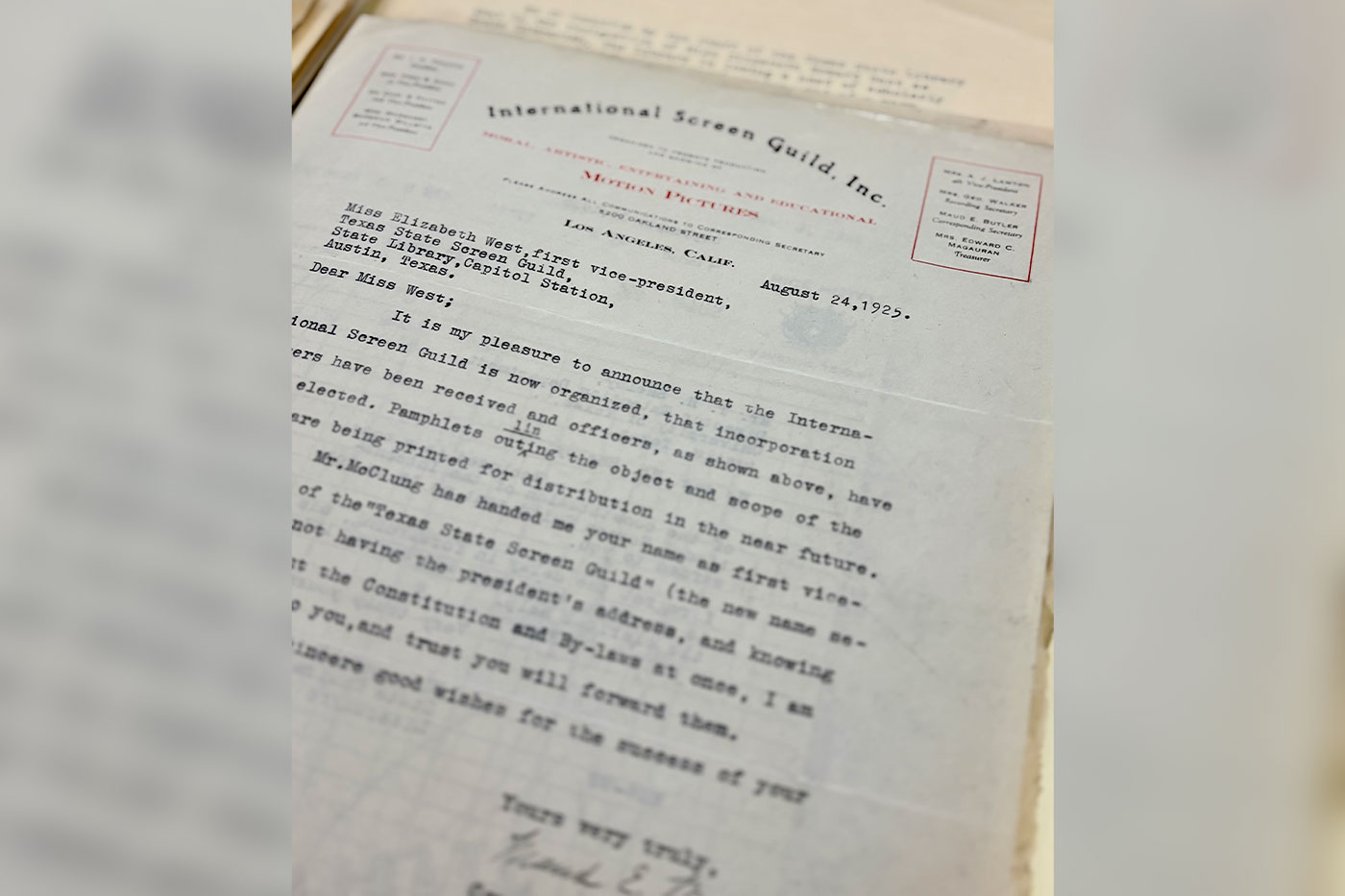

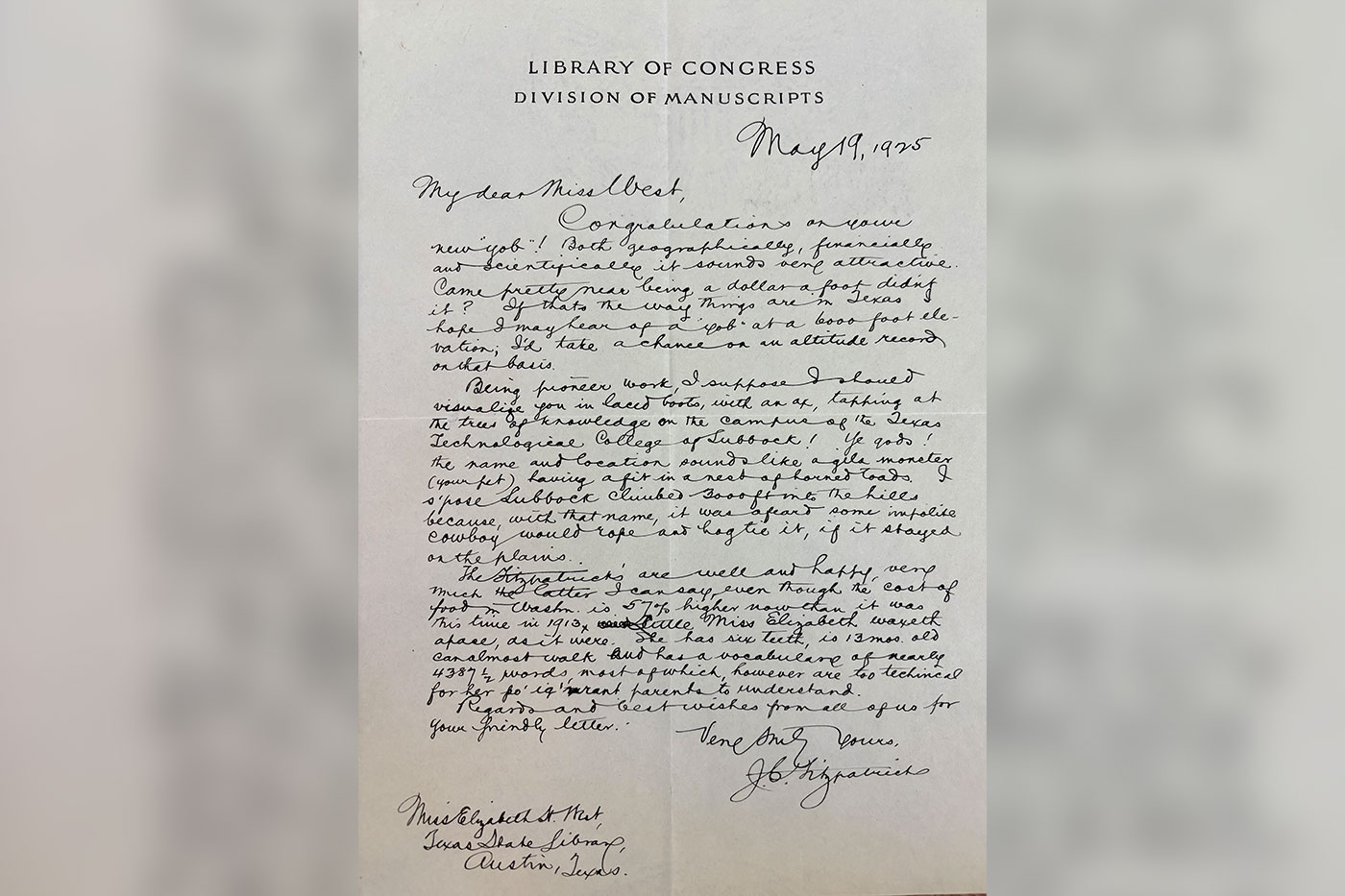

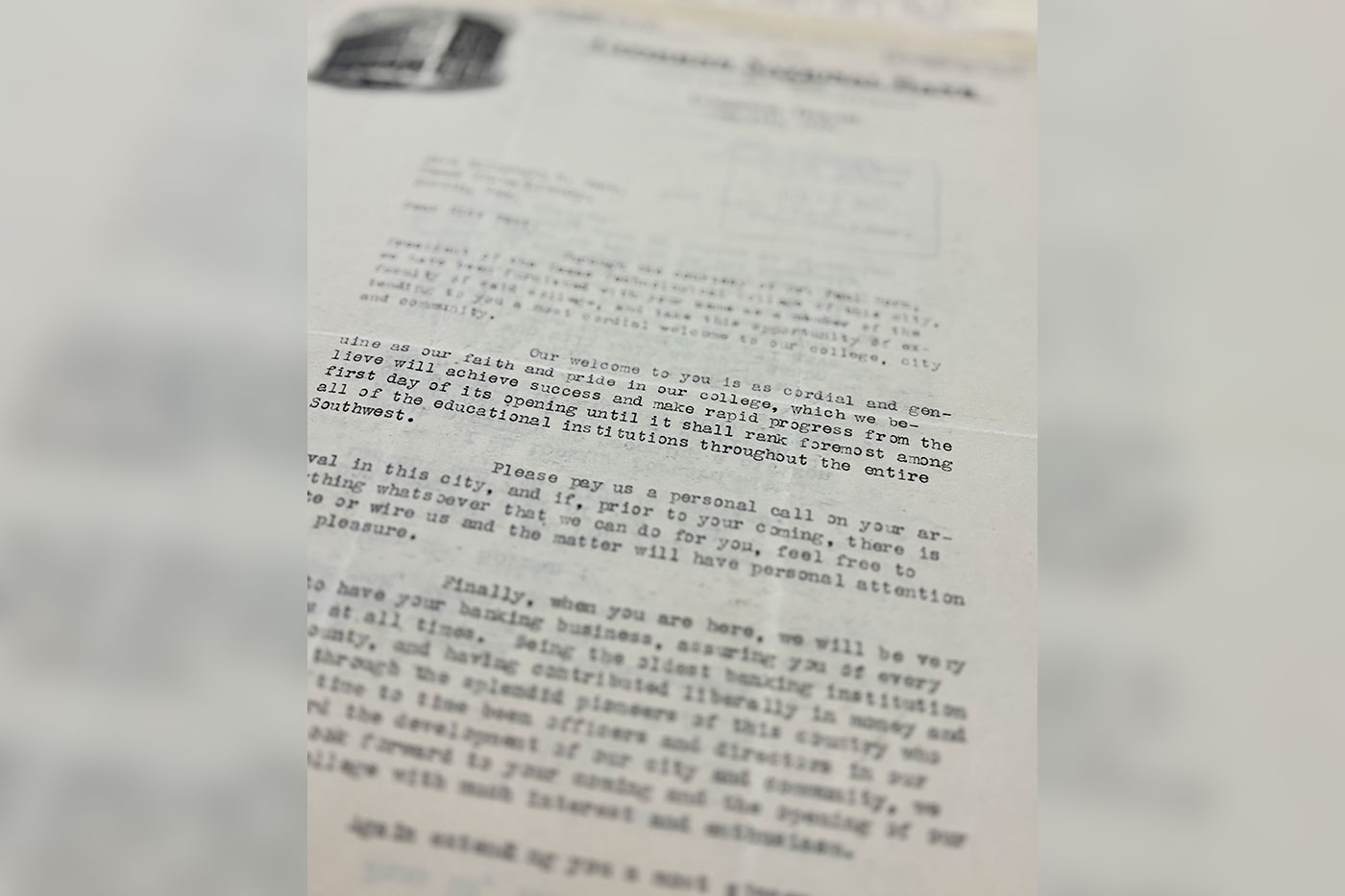

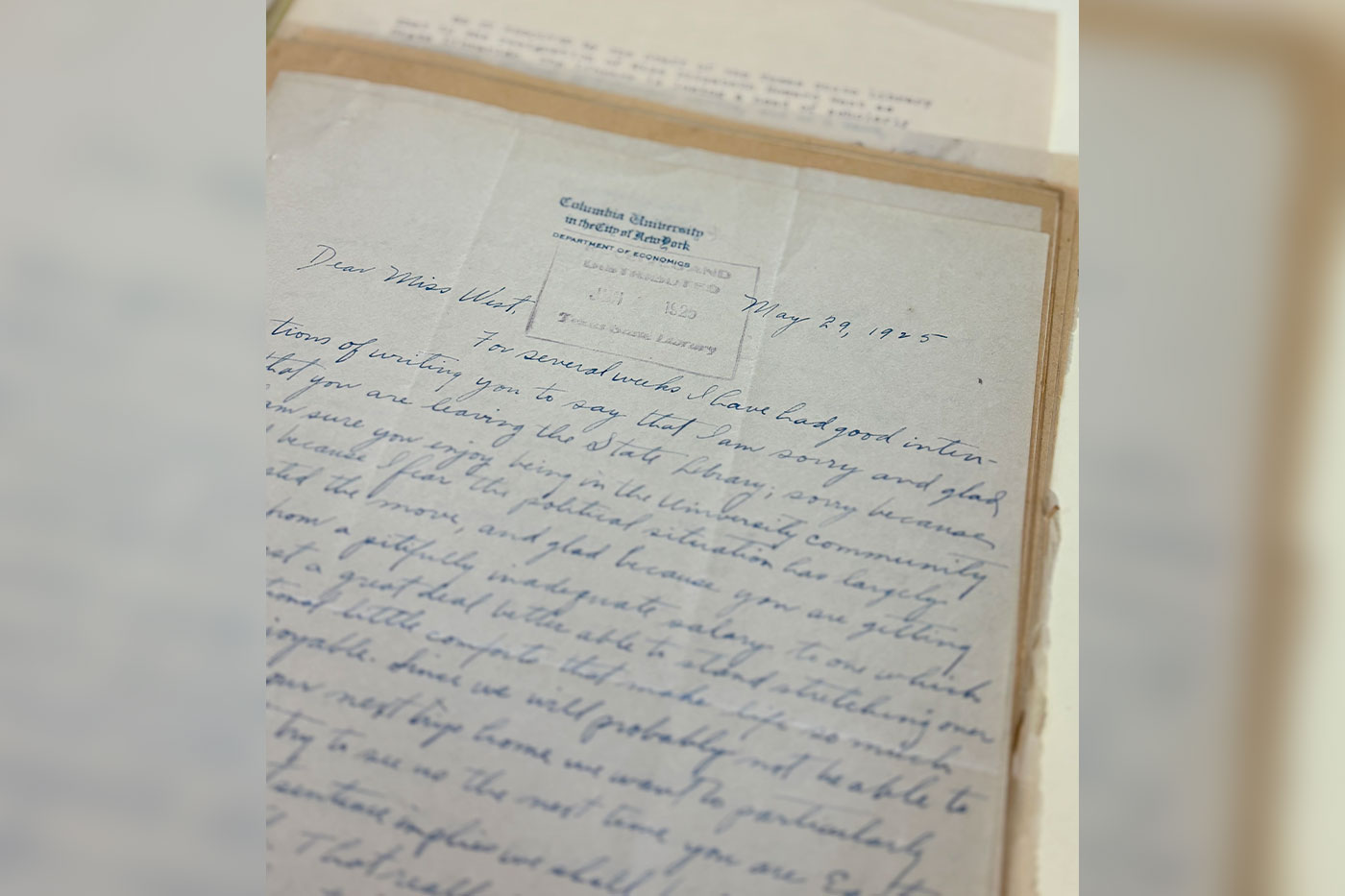

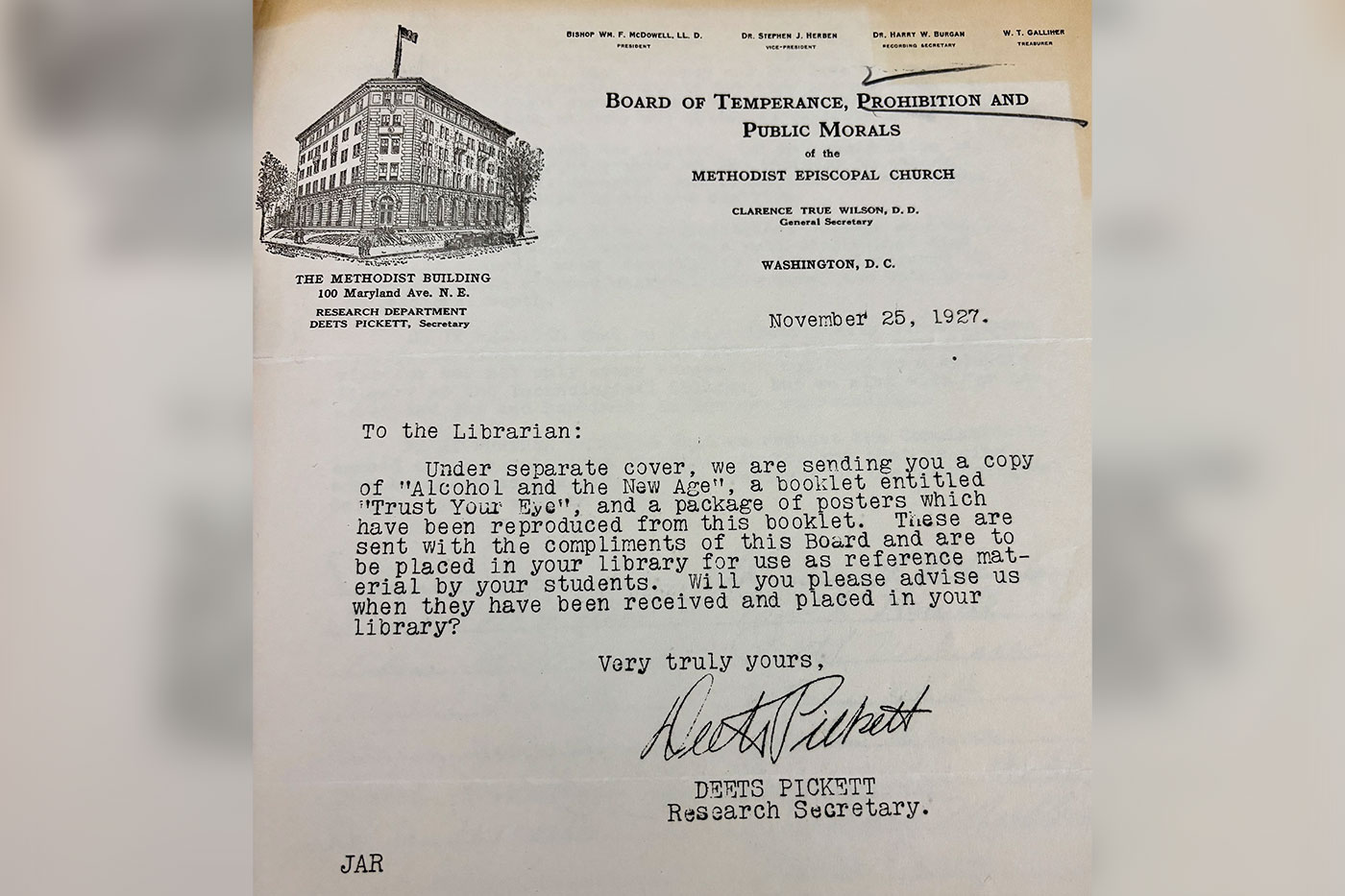

When news of her appointment spread, she received a profusion of written correspondence.

A friend from the Library of Congress wrote her, “Being pioneering work, I suppose I should visualize you in laced boots, with an ax, tapping at the trees of knowledge on the campus of Texas Technological College, ye gods!”

Rather, Elizabeth preferred flat, simple shoes, a man’s briefcase, and as far as trees go, there weren’t many to tap in the early days on campus. But the steadfast faculty member was unapologetic in her advocacy for her beloved books.

Magnolias and Blue Back Spellers

Elizabeth was born in 1873 in the small community of Pontotoc, Mississippi. Her father was the reverend of a small Presbyterian congregation, and her mother was a teacher. Elizabeth came from a long line of educators – her maternal grandfather, Moses Waddel, being a former president of the University of Georgia.

Elizabeth was the middle of seven siblings. She took to reading and writing as naturally as southern magnolias bloom through summer. When Elizabeth wasn’t tutoring her younger siblings, she could usually be found up a tree working in her Webster’s “Blue Back Speller.”

At a time when it would have been common to finish high school, marry and tend to a home, Elizabeth couldn’t see herself in that narrative. Instead, she ardently gave herself to her studies and enrolled at the Industrial Institute and College of Mississippi at the age of 15.

She took the position of schoolteacher in a small village in Mississippi after her graduation. She quickly surmised that no matter the dedication of the teacher, lack of quality texts and literature posed a considerable obstacle to any learner. So, in 1899, she entered the University of Texas and earned a second bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in history. She completed her library training there as well. Being on the campus of a large university with almost any book she wanted to read was akin to the Mississippian having gone to heaven. The access to world-class resources invigorated Elizabeth to teach again, this time staying close to Austin.

But in 1906 an opportunity opened at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. Elizabeth had originally been approached by Judge Raines, former state librarian, about a position with the state library, but the position had been promised to someone else. When he learned of the role in Washington, he used his resources to recommend Elizabeth.

She worked at the Library of Congress for five years, observing how one of the largest libraries in the world operated. She noted every feature and flaw, as if she had taken the hood off a Ford Model K and tinkered with every part of the engine.

She made her way back to Texas in 1911, after hearing about an open position as archivist for the Texas State Library. She spent a few years there before becoming the director of the public library in San Antonio, which at the time was The Carnegie Library – established with financial support from Andrew Carnegie.

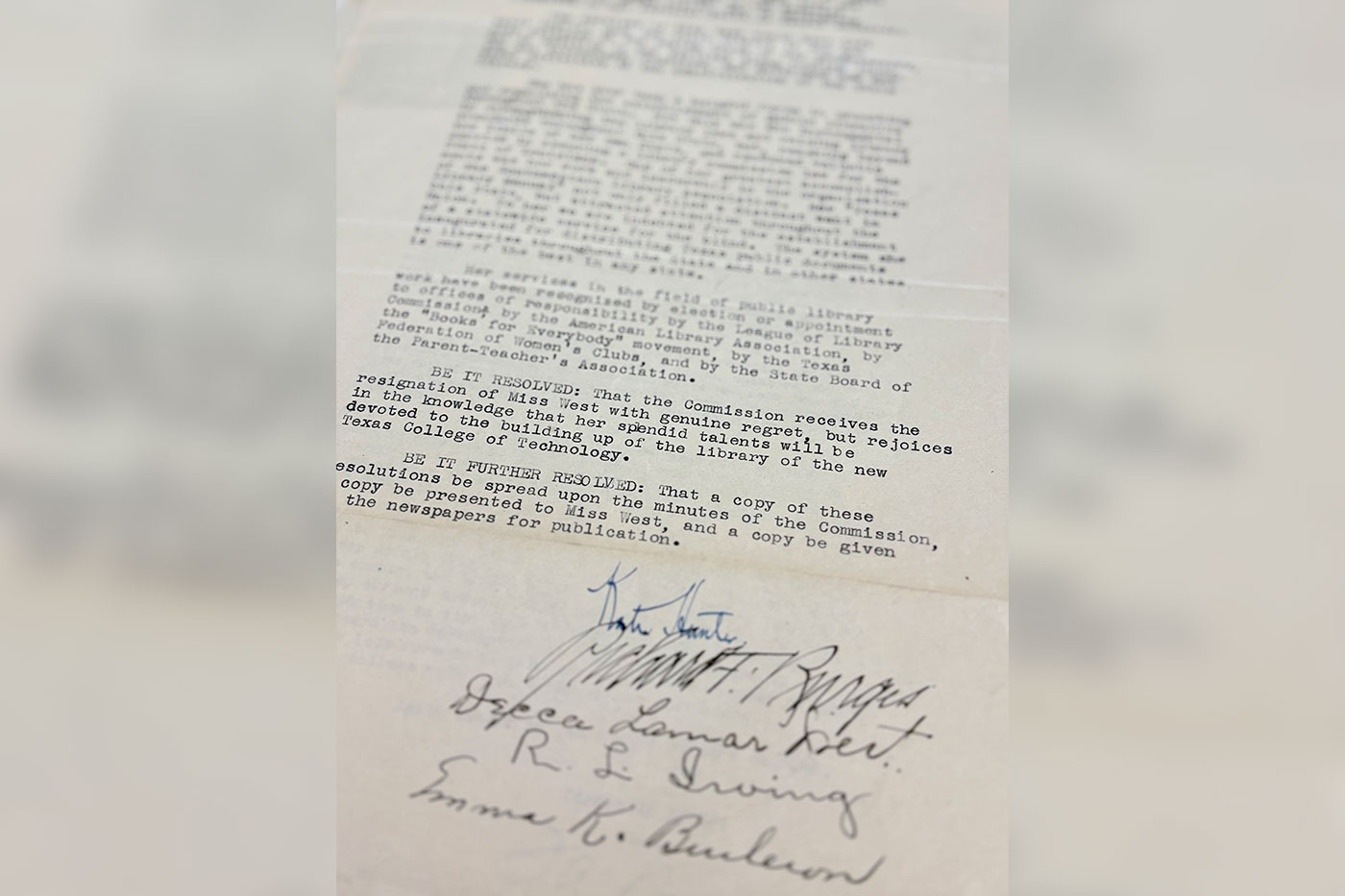

The position of Texas State Librarian became available in 1918, and Elizabeth was appointed, becoming the first woman to ever run a department at the state level.

“I think the legislature was having a difference of opinion with the man who was in the role,” said Janis Cochran Test, Elizabeth’s great-great niece. “Well, I think they thought putting a woman in charge would be easier on them; I think they were mistaken.”

While diplomatic, Elizabeth was not a pushover. She understood what needed to be done to bring the state library up to the level of service she knew it was possible of achieving.

These years in the state library were some of the most challenging, but fortifying times of Elizabeth’s career. With WWI unleashing its calamity, Elizabeth helped by creating the campaign for war camp library services as part of her role as President of the American Library Association – a role she served in for the benefit of others, but she found the public speaking “a horror.”

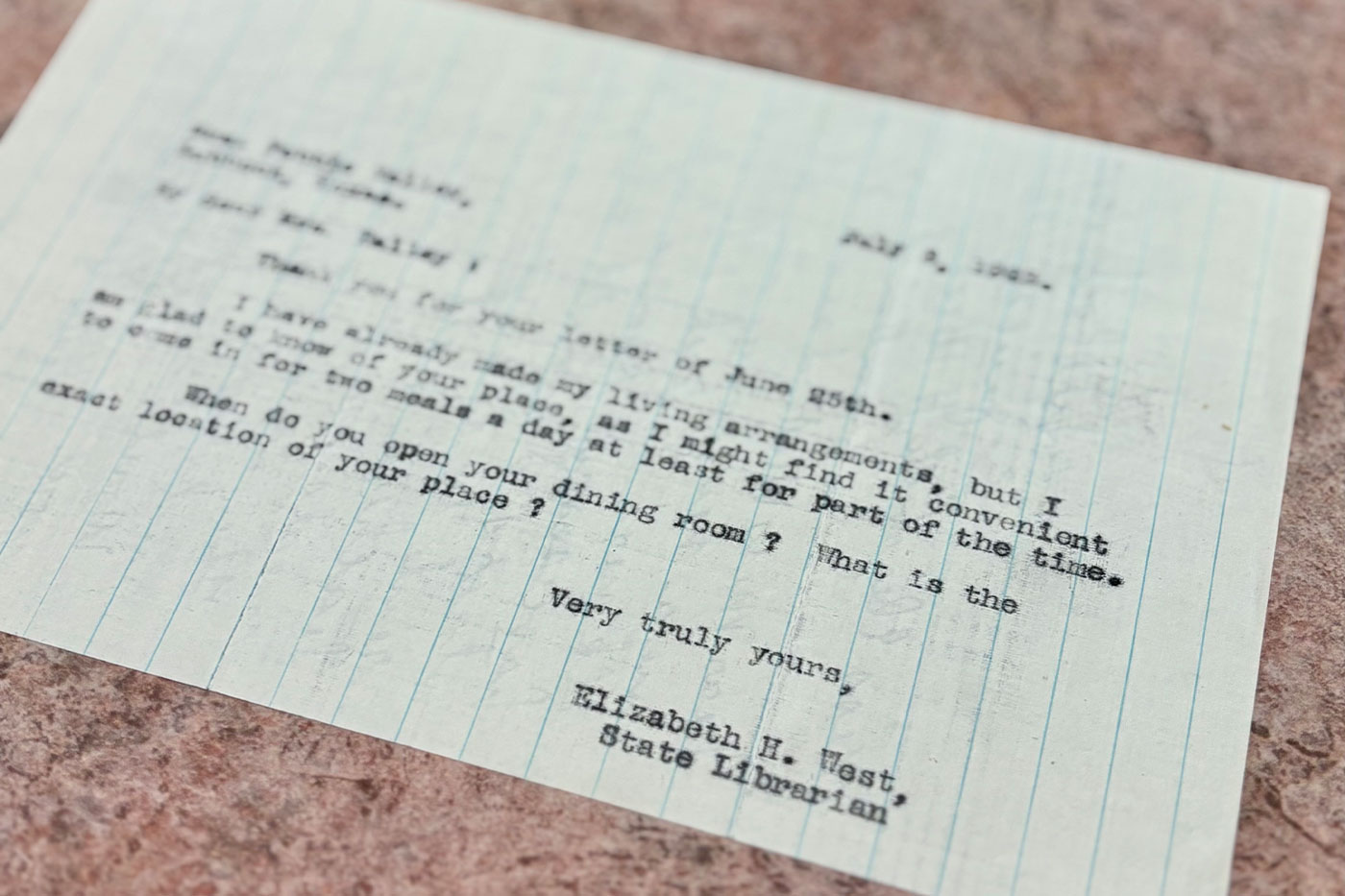

After the war ended and amid the rapid growth that the 1920s brought, Elizabeth was approached about taking the position of librarian at a brand new college being established in Lubbock, Texas.

“I think the idea of starting a new school sounded like an exciting challenge to her,” Janis said.

Moreover, the move to Texas Technological College came with an attractive pay raise and summers off to explore her own research.

Indefinite Expansion

While some of her colleagues were shocked, others agreed that it sounded like a grand adventure. Elizabeth had spent her entire career strengthening established systems – this would allow her to build one from the ground up.

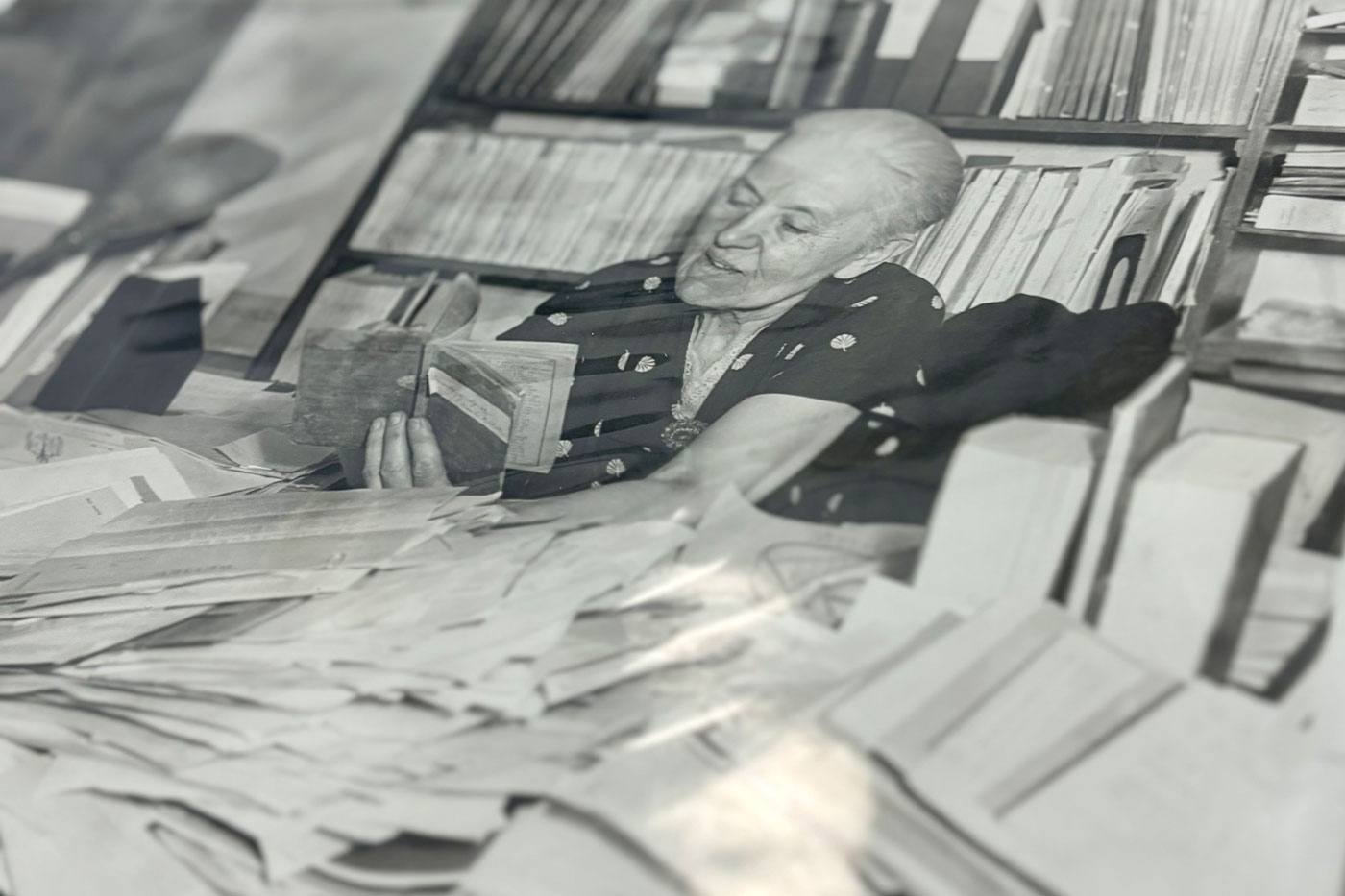

Elizabeth was one of the more senior and distinguished members of faculty. She arrived at the age of 52 with a remarkable resume already a credit to herself. Her reputation, mannerisms and even her stark white hair elevated her as not only a scholarly mentor but someone people naturally took into their confidence.

Elizabeth was of the mind that libraries should serve all people. This conviction complemented the sentiment of Texas Tech’s first president, Paul Whitfield Horn when he wrote, “My ambition for this school is that no man shall be so rich that he can buy anywhere a better education than we can give him and that no man or woman will be so poor as not to be able to take advantage of the education it will offer.”

Elizabeth got on with the task at hand, expeditiously acquiring volumes she believed would be relevant to students coming to the new school. There were novels and encyclopedias, collections of essays and texts on every manner of science, art, history and philosophy.

By 1928, Elizabeth wrote to President Horn, requesting more space for the library that was then in the administration building. Horn made it clear the possibility was at least one year away.

Elizabeth said that would not do. Sure enough, they outgrew their little tower in the administration building by the following month.

One of the challenges Elizabeth faced was getting others to anticipate needs for challenges that didn’t yet exist. She saw what Texas Tech’s early founders saw – endless possibility.

“I think Elizabeth recognized from the start that the lack of available research materials such as books and journals would pose a significant challenge for course instruction in the short term,” said Lynn Whitfield, archivist of the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library. “In the long term, it would be a hindrance to Texas Tech retaining academic accreditation and generating the quality of research necessary to bring in state and federal grant funding.”

Elizabeth wrote to a colleague at the time, “College libraries should be planned and situated in such a way as to provide for indefinite expansion.”

Eventually, Texas Tech got its first freestanding library, which most know today as the mathematics building. Elizabeth, a few assistants and roughly 40,000 volumes made the move across the quad.

But as the space was organized and cataloguing subsequently sped up, funding slowed down.

Elizabeth requested $265,000 for a book stock of 20,000 volumes.

The request was denied.

Leadership of Texas Tech had since transferred from Horn to President Bradford Knapp, who now had the position of listening to Elizabeth’s frustrations with funding choices. She was of the mind that state money primarily went to buildings and equipment, but rarely books.

She wondered out loud what would fill these new buildings. She worried that her goal to stock Texas Tech with world class resources was seen as nothing more than a “fantastical dream of a woman who was trying to magnify their job.”

These frustrations were only voiced to those she worked closely with, though. Elizabeth always chose the way of diplomacy to get what she felt the university needed. As the Great Depression unfurled itself with added stringencies, she drew upon the same determination she’d harnessed by teaching herself to spell up in the large maple and magnolia trees that skirted her family’s farm.

While she possessed an innate elegance, she was a true academic in the sense that she knew when to roll up her sleeves.

Despite the Great Depression, enrollment was not slowing down at Texas Tech.

She traveled to other universities along with state and municipal libraries, collecting duplicates. She even wrangled some from the Attorney General’s Office. Elizabeth had made friends everywhere she’d traveled, and they were all too eager to come to her aid.

She started a book club in the yard of her cottage near campus for students who wanted to discuss what they were reading or find books the library didn’t currently possess. Many students took her up on the offer, sitting out under the West Texas sunset and trading ideas over every subject they could find.

That wasn’t to say she didn’t socialize with other faculty members, but she didn’t often enjoy the same activities of her female peers. Ruth Horn remembers Elizabeth making a valiant effort to play bridge, for which she was unfit by temperament and training.

“But she was unfailingly good-natured when she was teased about confusing spades and clubs,” Ruth said.

Her Long-Lasting Legacy

Elizabeth, in many ways, was Texas Tech’s future made manifest.

And while it took many years to raise the funds for a permanent library, when the state finally approved a $275,000 appropriation bill in 1937, Elizabeth was said to have run outside, up the tower of the Administration building, and rang the Victory Bells.

Practically speaking, the largest legacy she left was the early decision to use the Library of Congress system. Because of her time in Washington, Elizabeth understood the benefits this system provided over the more widely used Dewey Decimal System.

While many municipal libraries are well served by the latter, academic institutions usually require the former.

“Library of Congress is preferred at academic institutions due to our audience and size of collection,” said Texas Tech Librarian Cynthia Henry. “It’s also better at greater specificity in subject breakdowns.”

Future innovation necessitates the ability to expand subjects – to make room for all the discoveries that are still to come.

Elizabeth’s early decision to put Texas Tech on the Library of Congress System has helped the university avoid a migration from the Dewey System like many other universities are now having to do. This has saved Texas Tech vast amounts of money.

Today, Texas Tech’s library comprises more than 2 million volumes. It offers access to 320 databases and houses everything from anatomy models to podcast studios to a virtual reality lab. Along with world-class faculty and nationally ranked programs, Texas Tech’s University Libraries is the heart of the institution – pumping knowledge and new ideas to every limb of campus.

“The vast availability of research materials and technical support offered by the University Libraries today, whether in-person or online, remain a contributing factor toward the university’s success in graduation rates, accreditations and grant funding,” Whitfield said. “This is Elizabeth’s long-lasting legacy.”

Texas Tech has grown from 1,800 students to more than 40,000, offering more than 150 undergraduate and graduate programs through its 13 colleges and schools. It’s also the only university in Texas to host medical, veterinary and law schools – all of which have specialized libraries that got their start through the resources created in the early days.

The almost 2,000 sprawling acres that make up Texas Tech, are likely a sight that would leave the beloved librarian of already few words – speechless.

Today, Texas Tech is categorized as a Carnegie Classification of Higher Education "Very High Research Activity” Institution – an achievement made possible through the same foundation that funded some of Elizabeth’s early work.

After she retired as librarian emeritus in 1942, Elizabeth remained in Lubbock, which had become her home. After suffering a heart attack in 1946, she moved to Florida to live with her sister Idelette.

She passed away Jan. 4, 1948.

The last time she saw campus it was much larger than the few buildings that dotted the horizon when she arrived. But everyone who knew her came to understand that she wasn’t impressed with buildings, unless they were filled with books.