Derek Rahn Williams took an unorthodox approach to finding his calling, but now that he has identified it, he is unstoppable.

Derek Rahn Williams will walk the stage at the United Supermarkets Arena for the fourth and final time this August.

But that was far from the plan.

Derek was enrolled at Clemson University in 2014 studying architecture when he got a phone call that veered him off course. Try as he might, he couldn’t stay on the path he’d once wanted so badly.

The following decade took him on a journey from the peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the flat plains of West Texas. Derek found a new, and in many ways, more meaningful path.

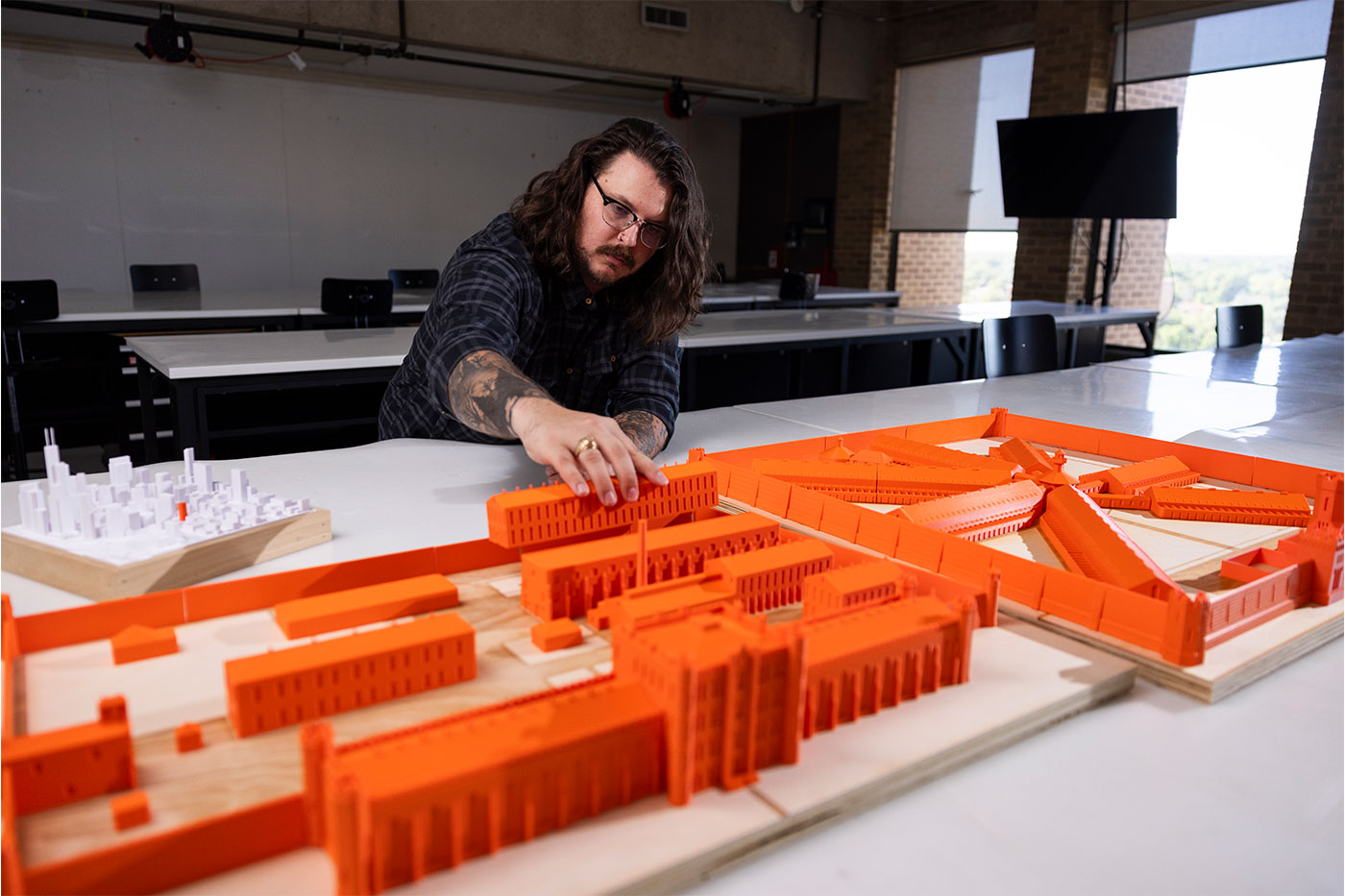

Graduating with a Master of Arts in architecture, interdisciplinary studies and sociology, Derek plans to teach at the collegiate level and continue his architectural research into carceral environments through a doctorate program at the University of Illinois.

But more than that, he hopes to use the support he gained at Texas Tech University to make a lasting impact for others.

The Plan

Raised in Greenville, South Carolina, Derek’s family was involved in their community. Derek’s father traveled internationally for his job in textile engineering and his mother had a public-facing job at a local hospital.

Derek and his younger brother Marshall were kind children who easily made friends. They both excelled academically and athletically. Derek was an active Eagle Scout, the vice president of his senior class, participated in various honors societies and lettered in cross country, track and swimming.

In 2012 Derek started college at Clemson University. He’d always dreamed of becoming an architect, so enrolling at Clemson’s School of Architecture was an easy choice.

“My neighbor was a home builder, and I was always fascinated with his drafting desk when I was over at their house,” Derek recalls.

It was just one of those things that drew him in; he wasn’t sure why.

“I’m good at drawing and I loved playing with Legos and Brio Trains,” he says. “But other than that, I’m not sure what it was that interested me so much.”

The skills needed for design were gifts Derek just inherently possessed.

The plan was simple.

Derek would earn his bachelor’s degree in architecture, and halfway through, Marshall would hopefully join him at Clemson, where his younger brother wanted to major in turf management and go into professional golf course management.

That was the plan.

The Unraveling

During Marshall’s senior year of high school, he was facing trouble with the law.

“The charges against him were deemed worthy of potential prison time; he was 18 and scared, and rightfully so,” Derek says.

The fear was so palpable that Marshall died by suicide Nov. 6, 2014.

“I just don’t think he could see beyond those circumstances,” Derek reflects.

His brother was old enough to face consequences but young enough to not understand life often affords second chances. His future began to shrink and fade until all Marshall could see was his mistake.

“Greenville has a small community vibe. Everyone seemingly knows everyone, and appearances are everything. I think Marshall couldn’t bear the idea of everyone finding out,” his brother adds.

Derek was in his junior year at Clemson when the tragedy occurred. He began to abuse drugs and alcohol himself.

“When Marshall died, I lost it,” Derek says. “I was so angry.”

Derek though, says he already had all the ingredients for unraveling. He’d started college with unresolved anger issues and depression. Unfortunately, losing Marshall was the catalyst for Derek’s unraveling. He managed to stay in school one more semester, but he struggled in and outside the classroom.

James Frazier Barker was one of his professors and mentors. Barker had previously served as president of Clemson but was teaching an architecture studio Derek was in.

“He knew what happened to my brother and he went to bat for me, trying to keep me from getting kicked out,” Derek remembers.

However, no one was able to take on the accountability that ultimately fell to Derek.

So, in 2015, Derek was suspended from Clemson. What ensued the following two years was a dance of getting back into school and dropping back out. Derek had moments of clarity, and his natural determination would come darting out. He even made the dean’s list the last semester he was at Clemson. But when pressed, he couldn’t stay sober.

At the end of 2016, he left Clemson for good.

“I ended up living out of my car,” Derek says. “I thought I was on some cool spiritual journey, dealing with my grief.”

But in hindsight, Derek calls it what it was.

“I was just using substances to avoid dealing with Marshall’s death, amongst other things,” he says.

After four months of driving aimlessly and sleeping at a campsite or even the side of a highway, Derek was ready for something different. His parents reached out and said they would pay for a rehabilitation program, but he had to come home and commit to getting sober.

Derek made his way back to South Carolina from Arizona, but instead of honoring his promise to his parents to return home, he ended up crashing on a friend’s couch nearby.

“A few days later, I would up in the hospital after totaling my car,” Derek recalls. “After that stint in the hospital, my parents dropped me off outside of Asheville, North Carolina, to sober up.”

Derek spent the following three months in a rehabilitation program set in the wilderness of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The program engaged his whole body in the work of healing. It forced him to face what was happening within, as well as helped him forge bonds with those doing the same.

The sense of belonging was integral to his recovery, which he was committed to – not only for his own sake, but to honor his brother.

The Path Forward

The two-sided sword of rehabilitation is that while community is key, finding or keeping that community after leaving can pose a challenge. His counselor knew Derek wanted to finish what he’d started with his architectural studies, but she also knew Derek needed a university that could support someone in recovery.

“She’d heard of Texas Tech’s Center for Students in Addiction Recovery and told me there was an architecture program at the university, too,” Derek says.

More than a program, Texas Tech was home to the Huckabee College of Architecture with one of the highest job placement rates in the country.

Derek dreamed of continuing his studies, but his parents were hesitant. They worried that the surge of freedom could land him in danger. So first, they paid for their son to move into a sober living house in Lubbock while he held down a job for a semester.

“I started over completely,” he says. “I flew to Lubbock with $26 and a pack of cigarettes.”

He remembers landing in Lubbock and wondering where all the trees were; uncertainty swirling around him like the dust covering the crop circles below.

“It was certainly nothing like the Blue Ridge Mountains,” he jokes. “But there was something serene about viewing those crop circles from a tiny plane window.”

Like the vast horizon before him, Derek sensed his future was opening wide.

Committed to Community

The first thing Derek did was build relationships at the Center for Students in Addiction Recovery.

“I accepted that I am an addict, and that’s always going to be a part of my story,” he says. “When you think you’re above it, that’s when you get in trouble.”

But Derek quickly learned that’s not where his story had to end.

The center is committed to students achieving higher education in an interconnected community. This also means students like Derek are seen in a holistic manner – emotional, physical, mental, academic, financial and even spiritual support is available to them.

“I was impressed by the campus, but also intimidated by how big it was,” Derek says. “It was hard to feel like I belonged that first semester. I was older than many of the other students in my classes and just felt out of place. So being a part of the center with other nontraditional students and having access to a smaller community that understood me was important.”

Derek had completed more than 100 hours at Clemson, so he wasn’t far from graduating with his Bachelor of Science in architecture. When he did so at Texas Tech in 2019, he knew he wasn’t finished. He had the confidence, support and vision he didn’t have the first time around.

He wanted to keep going.

“I moved to the West Coast for a short time, but COVID-19 hit which was isolating, and I was removed from my community I’d built at Texas Tech,” he remembers.

So, in 2021, Derek enrolled in Texas Tech’s Graduate School and earned two degrees – a Master of Business Administration and a Master of Architecture. In 2023, he began yet another master’s degree – this one in architecture, interdisciplinary studies and sociology. It’s the degree that will be conferred upon him this August.

From Loss to Leadership

People who meet Derek have a common question: Why so many degrees?

The answer is two-pronged.

First, Derek discovered his love of teaching when he became a part time graduate instructor. Second, it took Derek some time to merge his interests and his calling.

And that calling harkens back to Marshall.

Clifton Ellis, the Elizabeth Sasser Professor of Architectural History, worked closely with Derek throughout his graduate work and remarked on the creativity Derek possesses to utilize architecture for a greater good.

“Other students would do well to follow Derek’s example of dedication to expanding his own knowledge for the benefit of others,” Ellis remarked.

Rather than design homes or office buildings, which he could have done (he even had a job offer with a prestigious firm in Dallas), Derek decided to study the architectural decisions made in carceral environments. His mind often drifts to people like his brother, who could have spent time in prison.

Derek wanted to discover if the way prisons are designed actually helps in reforming inmates. He has also investigated similar questions for those in rehabilitation centers – another experience close to his heart.

“This was never the plan,” Derek recognizes. “I never saw myself turning down a job offer with a firm. Designing professionally was always a dream of mine.”

But the idea of affecting change on a large scale was an opportunity Derek couldn’t walk away from. Maybe he wouldn’t be helping inmates directly yet, but he wanted to be part of changing how incarceration is approached in the U.S. so that maybe, when a young person faces similar circumstances to Marshall, they see it as a process, not a final destination.

“It was clear immediately that Derek was a student I’d enjoy working with,” Ellis said. “He’s enthusiastic, quick to discern the significance of his readings and research, and very diligent.

“Our meetings about his work would always turn into wide-ranging conversations that I found fun and challenging. It was good to work with someone who was so keen and motivated.”

Other faculty had similar views.

Associate Professor of Sociology and Social Work Patricia Maloney first met Derek in her seminar on social theory.

“We start by going around the room and introducing ourselves and I was so pleased to see a non-sociologist in the room,” she said. “I was struck by how humble and interested in others’ perspectives Derek was, as well as how skilled he was at drawing out some of his shyer classmates.”

One of the faculty members who’s most proud of Derek though, is not at Texas Tech.

Former Clemson President and now Professor Emeritus James Frazier Barker reflects on his former student as a living example of the power of higher education.

“Derek is an inspiration to all students who face significant challenges,” Barker said. “His story of determination and talent is remarkable, and it is proof that every student can achieve their goals if they are focused and believe in themselves.

“In my office I display a drawing that Derek gave me. I keep it to inspire me and other students.”

Along with his research, Derek looks forward to continuing to teach and encourage students. He’s built strong mentorships with architecture undergraduates over the past years.

“We learn a lot together, but I’m also there for them beyond classwork,” Derek says. “I think students feel comfortable with me because I don’t look like their conception of a typical professor. I have long hair and tattoos.”

A part of Derek’s recovery that’s especially meaningful is showing up for others.

“I may not be able to hold a student’s hand through everything,” he says, “but if I can be the one to pull them back up and show them that they can keep going, that’s what I’m going to do.”