A new study co-authored by a Texas Tech marketing researcher shows that information on menus and nutrition labels may not lead to healthier choices.

Calories. We see them on display everywhere from the nutrition labels on products to the items on menus. Many of us will evaluate a food’s healthiness based on the number of calories, but does that mean we are making healthy decisions?

This question is at the heart of a new study co-authored by Deidre Popovich, associate professor of marketing at Texas Tech University’s Jerry S. Rawls College of Business. Popovich and co-author Ryan Hamilton (Emory University) argue knowing the calorie content of foods does not necessarily lead to consumers making healthier judgments. In fact, it can often lead to the exact opposite.

In “The Illusion of Calorie Fluency: How Metacognitive Uncertainty Leads to Less Extreme Healthiness Perceptions of Foods,” the researchers conducted nine experiments with over 2,000 participants to analyze how people use calorie information while evaluating food.

In the first experiment, participants were divided into three groups and asked to rate the healthiness or unhealthiness of foods such as salads or cheeseburgers. The control group did not receive any calorie information, the low-salient group received calorie information in a small font and the high-salient group received the calorie information in a more prominent, large font.

While the control and low-salient groups accurately evaluated the gap between healthy and unhealthy foods, the high-salient group did not. They were rating salads as less healthy and cheeseburgers as less unhealthy.

“When you ask people to think about calorie counts, everything suddenly gets rated more in the middle of the healthy scale,” said Popovich.

Over the course of the next eight experiments, the researchers consistently saw participants become less confident in their ability to accurately judge food’s healthiness when using calorie information. This uncertainty led to participants judging the food moderately.

Participants were used to seeing calorie information in their day-to-day lives and developed a false sense of familiarity. Or as the researchers put it, participants had an illusion of calorie fluency.

However, the moment participants were tasked with using that information to make a judgment on food, their confidence in that fluency suffered greatly.

“People think because we have calorie information everywhere it should be easy to use, but it’s not,” said Popovich. “It actually can be more confusing to use that information and can be problematic if you really start thinking about it and engaging with it.”

Popovich likened what was happening in their experiments to other purchasing decisions, like buying a smartphone. As consumers, we may see a new smartphone camera with 48 megapixels and assume it is better than the smartphone with a 24-megapixel camera. After all, more is always better, right?

But the moment we are asked to explain why higher megapixels are important or what role megapixels play in our photos, our confidence in our knowledge can plummet.

“Manufacturers list the product attributes, and the assumption is you know what these things are and how you’re supposed to use them,” said Popovich. “To the lay consumer, most people can’t decipher that information in a meaningful way, and it might skew their perceptions of how good the camera or food item is.”

Making Healthier Choices

Popovich hopes this study can have an impact on the public health sphere in several ways.

“One of the reasons I undertook this research project is because calorie counts have been mandated for a long time, and you can see what happens to the obesity rate after that,” Popovich said, noting that obesity rates have increased since nutrition labels were mandated in the U.S. in 1994. “This wouldn’t be happening if it was truly about information access.”

The researchers urge retailers to provide a better understanding of how their customers use and are affected by calorie information. Retailers could guide customers to healthier choices by de-emphasizing calories and focusing more on nutritional benefits (e.g., “packed with antioxidants” or “good source of fiber”).

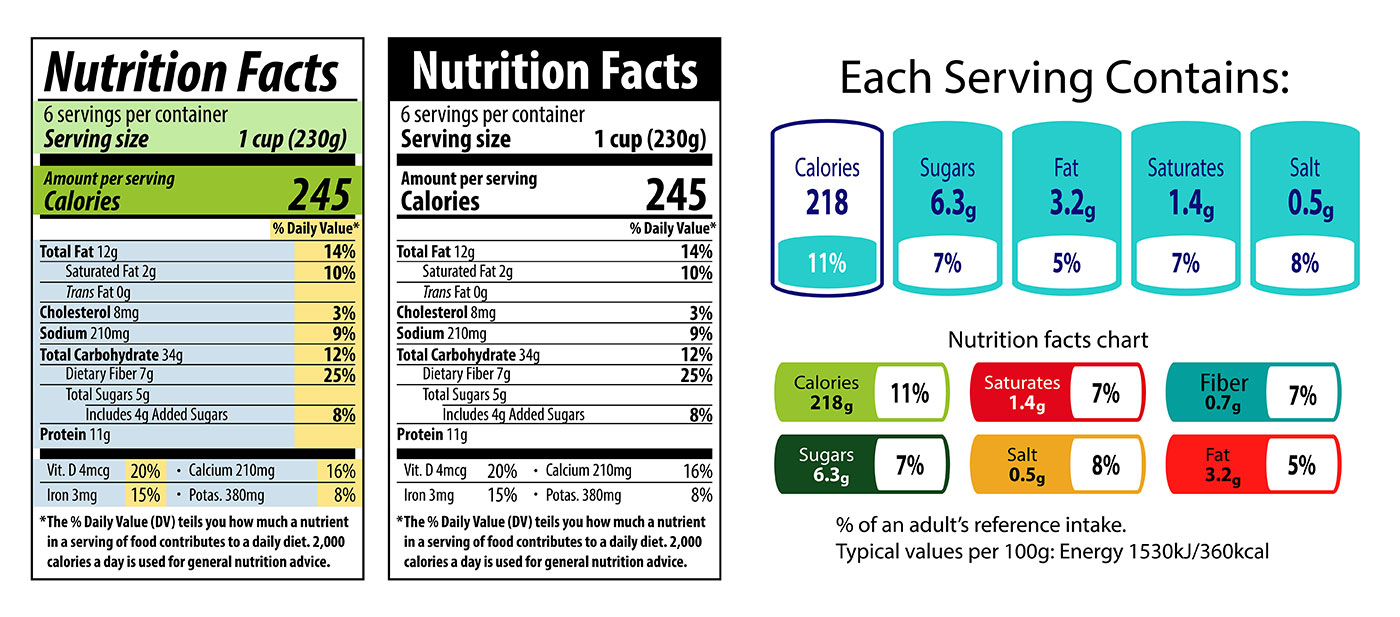

For marketers and companies wanting to engage in acts of transparency, their efforts cannot end with giving consumers information – they should provide additional context or clarity. For example, the number of calories in a product could be shown as a percentage of the recommended daily amount, similarly to what we see with other parts of a nutrition label.

Consumers should develop their actual nutrition knowledge to break the calorie fluency illusion and make more accurate judgments.

“This research demonstrates that the illusion of calorie fluency arises due to consumers’ realization that they don’t know as much as they thought,” wrote the researchers. “Conversely, for consumers who rate themselves high in nutrition motivation, the effect goes away.”

At the very least, consumers should trust their instincts when judging the healthiness of food. This means having some understanding of their target caloric intake and considering multiple nutritional aspects like fiber, cholesterol, protein and more.