Jere Lynn and Jim Burkhart’s perseverance to find help for their autistic grandson inspired them to found the Burkhart Center for Autism Education & Research.

Jere Lynn and Jim Burkhart’s home is quintessentially Texan – which makes sense for the couple who grew up in the small community of Hamlin.

The reds and browns of their furniture are intermixed with leather and the occasional cowhide providing a warm and comforting feeling as soon as you walk in the door. Walls are covered with Western art, and shelves in every room are packed to the edge with family photos.

The pictures capture defining moments of the Burkharts’ lives. Their wedding in 1952. Jim in his Texas A&M University football uniform, a proud “Junction Boy” playing for the legendary Coach Bear Bryant. Photos of their children as they aged from infants to toddlers, and from teenagers to adults with families of their own.

There are images from their homes in College Station, Oklahoma City, Chicago and all over Texas, capturing moves that followed the progression of Jim’s career in the oil and gas business.

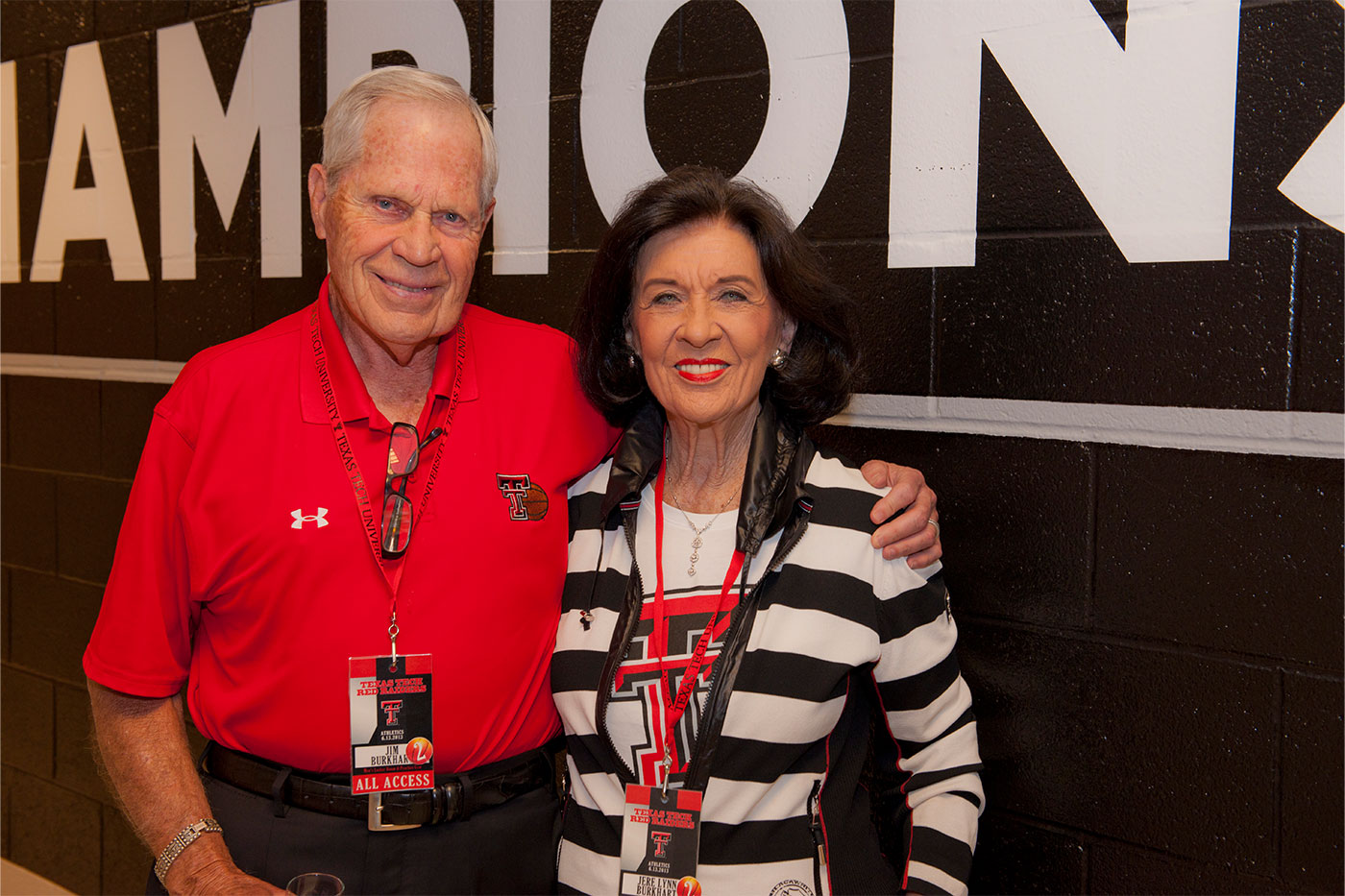

While their faces age through the photos, Jim still carries the ornery glint in his eyes, and Jere Lynn still dons her jet-black hair and impeccable red nails and lips as they recount the twists and turns their lives took over the past 72 years.

“We've been blessed, I guarantee,” Jere Lynn said with a beaming smile pointed toward her husband. “Blessed with a lot of surprises, but it never bothered me because I knew how smart Jim was!”

A Learning Curve

One of the greatest surprises and blessings captured proudly in many images is their grandson, Collin Burkhart.

Collin was born in 1984 to their son Keith and his first wife. Collin often stayed with Jere Lynn and Jim because Keith worked for an oil and gas company and spent a considerable amount of time on rigs at various sites. Then, when Collin was 2 years old, he came to live with his grandparents and was adopted by them shortly after.

Jere Lynn quickly knew something was different about their sweet grandson.

“I knew something was wrong at about six months,” she said. “I knew that he wasn't talking. He couldn’t walk. He wouldn’t pick up anything like most babies do. He was different. They took him to a pediatrician, but the pediatrician would not acknowledge anything was wrong. Nobody knew about autism then, not even the doctors.”

They were in their late 40s and living in Tulsa at the time. Jim was just starting a new company, and Jere Lynn was working as his secretary. However, from the moment Collin made the permanent move to their home, Jere Lynn began an impassioned mission to help her grandson.

Their first endeavor was to teach Collin how to sit up. Jere Lynn would lay out a big quilt on the floor and they would prop Collin up with pillows, supporting him with their hands and gradually reducing the pillows until he could sit up on his own.

Next on the agenda was learning to crawl.

“He learned to crawl with us down on our hands and knees, one of us holding his hands, and the other holding his legs,” Jere Lynn said. “He was almost 2 years old and couldn’t crawl and didn’t walk.”

“Oh, but you were determined to get him crawling,” Jim smiled as he replied pointing at his wife. “She’d get the toys he wanted and put one on each corner of the quilt and make it where he had to move if he wanted to get them.”

“He’d kind of scoot toward the toys…,” Jere Lynn started.

“But then he got too smart for us,” Jim interjected as the couple laughed remembering Collin’s trick. “He started pulling on the quilt until he got the corner all the way to him and got his toy.”

Throughout all this time, the Burkharts were searching for experts to help them figure out the best ways to care for their grandson.

Their research started with local pediatricians. Jere Lynn’s hairdresser pointed her toward a local pediatric specialist who focused on children with developmental delays, and she made an appointment.

“That was the first doctor that spent a whole Saturday afternoon with him on the floor to see,” Jere Lynn said. “He told me, ‘Yes, he is autistic, but we don’t want to put that word on him.’”

The doctor was reluctant to officially diagnose Collin because autism was not yet recognized under what was then the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA). Prior to the enactment of EHA in 1975, only one in five children with disabilities had access to an education in the U.S., and many states had laws that excluded certain students with physical, mental or social disabilities from attending public school.

Autism would not be added to the program until it was reauthorized in 1990 and was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). So, at the time of Collin’s diagnosis, he was not guaranteed access to education. Additionally, Jere Lynn said the state of Oklahoma would not help with the financial burden of sending him to a private school for the specialized education he needed.

Despite the difficulties she knew were ahead for their family, Jere Lynn was not deterred. They had discovered a psychologist and professor of special education at the University of Oklahoma, Dr. Diana Mobley. Dr. Mobley was a leading expert in the state on autism, and in a time when the disorder was understood by so few, the Burkharts knew they needed to meet her.

Jere Lynn made the call, and they took Collin on the three-hour drive to Norman to meet Dr. Mobley. After spending an entire afternoon with Collin, Dr. Mobley confirmed the autism diagnosis. She offered the Burkharts a lifeline: If they could bring Collin to see her every Saturday, she would work with him for several hours. They readily agreed.

In addition to Dr. Mobley, Jere Lynn and Jim sought help from experts at universities across the country. This included a professor from the University of Arkansas who spent an entire week at their home working with both Collin on his motor skills and his grandparents on methods they could use to help him.

Teaching Others

When it came time for Collin to start school, Jere Lynn knew there was only one place she wanted him to go. There was a school in Tulsa that exclusively enrolled students with developmental delays. Additionally, along with teachers, they employed physical therapists, speech therapists and other medical professionals. She worked diligently with their local pediatrician to get Collin enrolled.

However, the school required parents and guardians to come tour before their child started classes because the administration knew it could be an emotional experience for them.

“We knew that was where Collin needed to be because by that time, I was having other people come to our house to work with him,” Jere Lynn said. “He just needed more help than what we could provide.”

Collin’s first days of school were challenging for the family. Collin was around 4 years old when he began and had been placed in a classroom with other students his age. While Collin was non-verbal and could not walk well, other students in his class were walking and talking. For Collin, this was a huge adjustment to be surrounded by so much noise and movement, and it greatly upset him to the point that he would cry each day on the way to school.

“After a few days, I had decided to take him out of school,” Jere Lynn said. “Bless his heart. He knew he was going to that school, and he didn't want to.”

However, the superintendent had one more plan to try before Jere Lynn took Collin out of school. There was a classroom they believed would be less overwhelming for Collin because it included students who were less mobile than their peers of the same age. Jere Lynn walked into the new room to see a large classroom with students seated throughout, a small TV and two low shelves of toys.

“We took him in there, put him on the floor, and he crawled as fast as he could to those toys,” Jere Lynn said. “He grabbed a toy, and he didn’t cry. He had full range of the room and was happy as he could be for the rest of the year.”

While Collin progressed significantly over his first year in school, Jere Lynn and Jim knew they wanted to continue his progress over the summer and set the task of teaching him to walk.

Around his fifth birthday, a friend had given Collin a small, blow-up, plastic ball that had become his favorite toy. He would spend hours playing with it, and Jere Lynn noticed he had begun to try to pull himself up into a standing position on the ball.

“One day I was at the grocery store, and I saw this sturdy, blow-up ball that was 36 inches, and I bought it,” Jere Lynn recalled. “I said, ‘I’m going to get that little boy to stand up on that ball. It’ll roll, and he will go.’”

She brought the ball home, Jim blew it up and they pushed back all the furniture in their living room to give Collin space. Then, Jere Lynn helped Collin stand up and hold onto the ball.

“Oh, he was just so happy to be standing and holding on to that ball,” Jere Lynn said with a wide smile. “Then, guess what? One day it rolled a little bit, and he took a step. And it rolled a little bit more, and he took a step.

“He kept holding onto that ball, and he finally got all the way across that living room. Just to keep his ball, he was walking. Then one day it rolled away from him, and he just kept going.”

Jim shared not only his wife’s fondness for their grandson’s first steps, but also his respect for Jere Lynn’s ingenuity and tenacity.

“That was one of the neatest things that she did,” Jim said as pride shone in his eyes.

Jere Lynn and Jim were not the only ones who were impressed with Collin’s new mobility. When Collin arrived back at school in the fall and proudly walked across the gym in front of all the classes and teachers, he was met with a roar of applause and cheers.

“He was a star that day,” Jere Lynn said.

Just as with his first year of school, Collin and his grandparents faced difficulties each time Collin entered a new classroom or had a new teacher. From his elementary education in Tulsa and into his junior high and high school education after they had moved to Lubbock, each transition brought up the same problem – many educators lacked the knowledge of how to teach a student with autism.

Collin was incredibly intelligent but non-verbal and struggled with fine motor skills, meaning that while he understood what was being taught in the classroom, he did not display the verbal or written skills other students used to communicate with his teachers. The couple often had to bring in specialists they had found early on in their own research or come in themselves to help train Collin’s educators on methods to teach, interact and communicate with him.

“He just amazes us, how smart he is,” Jere Lynn said. “He’s found so many ways to communicate with us. But school systems did not know much about autism, and he needed special help.”

Education and Resources for All

From the time they adopted Collin to today, the Burkharts have been staunch advocates for not just their grandson, but all those in the autism community. When he was born in 1984, most people knew little to nothing about autism – including doctors and teachers. This meant if they wanted to find help for their child, then they had to pour significant efforts and finances into locating information and experts who could provide answers.

“What do you do when a doctor tells you your child is autistic?” Jim asked. “Believe me, back then it was a big black hole. We paid people, we brought in experts, and we learned one piece at a time, but not everyone can afford to do that.”

While they met this challenge head on, they did not want others to have to do the same. Their original thought was to create a place with two purposes: an educational center where teachers could learn classroom approaches to educate students with autism and a location where parents could access all recourses available about how to care for children with autism.

Because of their positive experience with professors who helped Collin in his early years, and knowing many universities had special education programs, they knew off the bat they wanted to establish this program at a university. While the Burkharts had originally debated between Texas Tech University and another university to house their idea, a conversation at a Texas Tech football tailgate in 2003 quickly confirmed their choice.

The Burkharts had tentatively proposed their idea to Texas Tech leadership before happening to sit by Robin Lock, Ph.D., and Carol Layton, Ed.D., two special education professors in the College of Education, at the tailgate. The group’s conversation quickly turned to Collin and the Burkharts’ interest in educating teachers and parents about autism.

Lock and Layton quickly gave the idea the push it needed to become reality and were sitting with the Burkharts in their home with a proposal within the week. The conversation resulted in a $65,000 gift to provide one classroom and training for educators to learn how to work with students with autism, and teachers from around the South Plains began to travel to Lubbock to receive 10 to 12 weeks of training.

“That was the beginning of a very long and wonderful partnership,” Lock said. “You know, it was one of those things where, initially, it was a nice amount of money to do a specific project, and then it just grew and grew and grew.”

And grow it did. From their initial gift in 2003 to today, the Burkharts have given over $10.5 million to support autism education and research at Texas Tech, and the one classroom has grown into a robust center dedicated to supporting families, teachers and students.

The Burkharts’ original project transformed into the Burkhart Center for Autism Education & Research in 2005, and thanks to their continued generosity and the support of other donors, the center opened a new headquarters in 2013.

In addition to the upgrade in location, the Burkhart Center is now home to robust services for educators, parents, college students and more. Their services include the Teacher Training Institute for educators; on-site programs, telehealth clinics and mobile outreach clinics for families; and CASE and Transition Academy for college students; just to name a few.

The growth that has come out of their initial conversation is something Jere Lynn and Jim, despite their hopes, never imagined would come to fruition.

“I never imagined it would grow to the extent it has,” Jere Lynn said. “When it started out, I just wanted to be able to train teachers to know what an autistic child is like, but the secret to our success has been the good people who have been involved. I didn't envision this. I didn't envision a building. I just wanted maybe a program in the College of Education to help teachers. So, it's far exceeded that.”

While Jere Lynn is amazed at the expansion and impact the Burkhart Center has had in the last two decades, Lock said the same tenacity that pushed Jere Lynn to advocate for her grandson is why the Burkhart Center is where it is today.

“If you knew Jere Lynn Burkhart the way I know Jere Lynn Burkhart, there’s nothing surreal about it,” Lock said. “She is one determined woman, and she had a lot of faith in us. I’ll admit that sometimes you just stop and go, ‘Oh, wow. That is beyond my wildest dreams,’ but at the same time, I know it was what Jere Lynn wanted. So that's why it seems so natural and real to me.”

This feeling is shared by many of the Burkhart Center staff who have had the chance to work with Jere Lynn and Jim over the years.

Susan Voland, who has worked at the Burkhart Center for 16 years, has a daughter who participated in the Transition Academy.

“Jere Lynn is truly an amazing woman who has made a difference in the lives of many, Voland said. “She is one of the kindest and most compassionate people I know. Her care and concern for everyone, and especially those with autism, is obvious as soon as you meet her. Her involvement in the Burkhart Center has been personal, and she has made it her mission to see the center succeed.

“Without the Burkhart Center, my daughter would not be where she is today,” Voland continued, “thriving as a young adult who has a job and social connections. The services that she has received over the years have made a tremendous impact not only on her life, but also in the life of my family. I will be forever grateful to the Burkhart family for all they have done for the autism community in West Texas.”

Janice Magness, a longtime friend of the Burkharts, was the director of the Transition Academy for 15 years.

“They provided so much to this whole community,” Magness said. “I know this because I’ve been with Jere Lynn at the grocery store and total strangers will come up to her and say, ‘Are you Miss Burkhart? My son or daughter was at the Transition Academy, and you just have no idea how that helped us.’ There’s no end to the influence that they have had, and we may never know it, but it's been amazing.”

Jennifer Hamrick, the current director of the Burkhart Center, is amazed by the resounding impacts the Burkharts have had in the autism community.

“I’m amazed every time Jim and Jere Lynn tell their story and they tell what they have done to help Collin throughout life,” Hamrick said. “I'm grateful for not only myself but for the West Texas community as a whole for their generosity, because there are thousands of families that would not otherwise even have a single resource if it weren't for the Burkhart Center and for Jim and Jere Lynn.”

From Burkhart Center staff and Texas Tech leadership to countless families and educators, the Burkharts have undoubtedly paved the way for autism awareness, education and research, not just in West Texas, but across the country. To honor their contributions and Jere Lynn’s steadfast determination for this community, Texas Tech University will present her with an Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters during the May 2024 commencement ceremonies.

"Few have impacted Texas Tech University and the greater West Texas region as Jim and Jere Lynn Burkhart have," said Texas Tech President Lawrence Schovanec. "This honorary degree acknowledges Jere Lynn's passion for supporting those with autism and reflects the extraordinary service and generosity that exemplifies the Burkhart legacy."

However, despite the countless praises, honors and thank you’s Jere Lynn and Jim have received over the years, they always point back to the beginning, back to the little blessing and surprise that changed their lives and the lives of countless others for the better.

“I tell people how important things are that you never think about,” Jim said. “That little boy, who's now a young man and who probably wouldn't impress you very much, has touched more lives than all the rest of our family and our friends and everything put together. Because without Collin, I have to admit, I doubt that there would be a Burkhart Center. But because of Collin, all of these things have transpired.”

Support the Burkhart Center

This April, during World Autism Month, join the Burkharts in their mission to help those impacted by autism by supporting the Burkhart Center. For more information about the services offered by the Burkhart Center, visit its website.