Two teams comprising undergraduate and graduate students traveled to Switzerland to test a device developed at the university.

Once there were four young kids growing up in separate parts of the country with very different backgrounds. One was a girl who grew up bonding with her grandfather over science shows on television, math and other related topics, not realizing until she was much older that she loved science.

A young man who says he was not always the best student discovered in high school that he might be interested in pursuing physics. Another youngster who grew up in Geneva – Illinois – not far from the United States’ own particle physics laboratory, wasn’t ever interested in what was going on there until a gravitational pull led him that way.

And another child who loved asking questions and reading books figured out by middle school she was fascinated with astrophysics.

The futures of these four youths – Caitlin Tidmore, Miles Harris, Valdis Slokenbergs and Elizabeth Veraa – have collided in Texas Tech University’s Advanced Particle Detector Laboratory (APDL) housed in the Department of Physics & Astronomy.

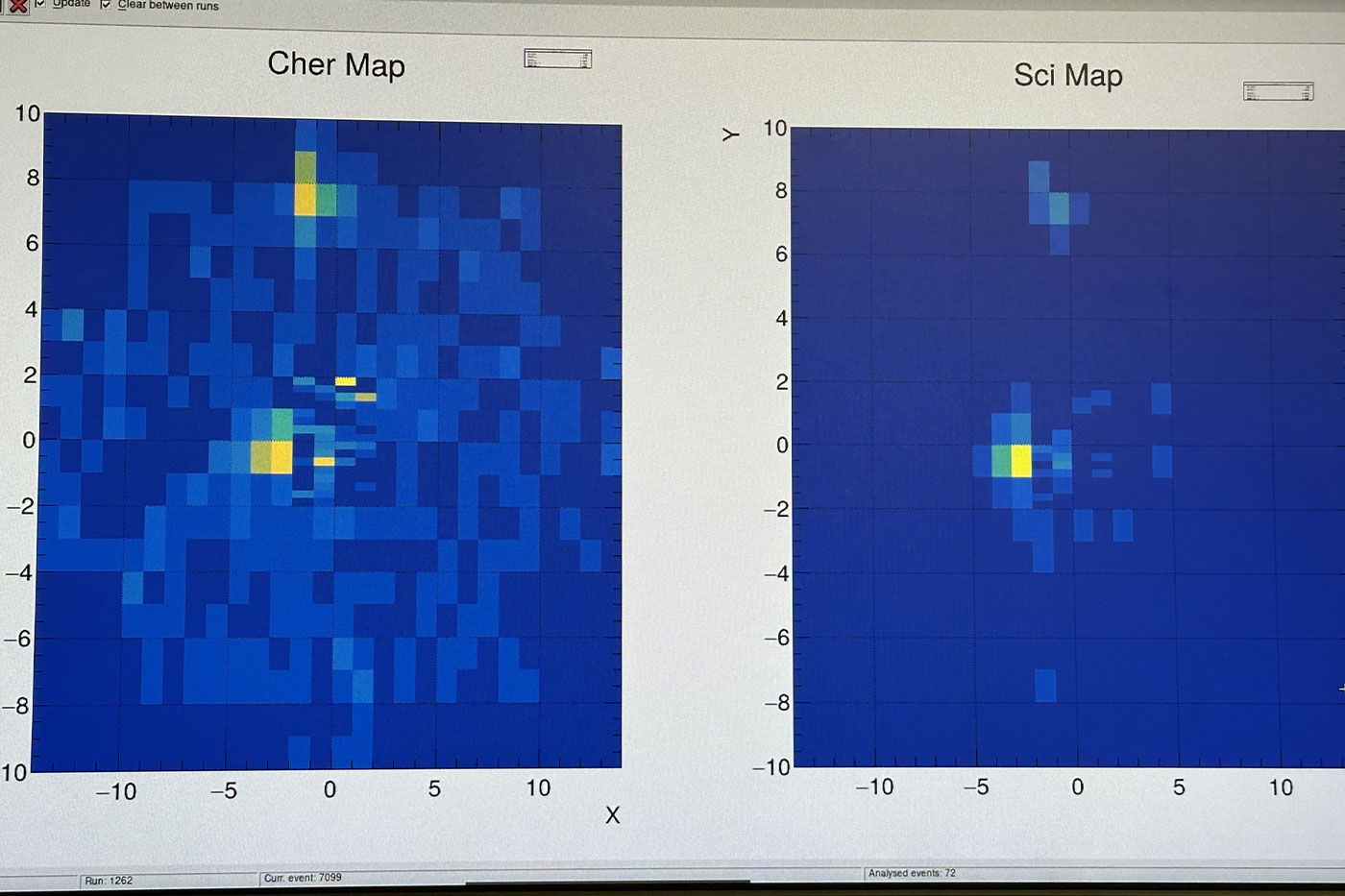

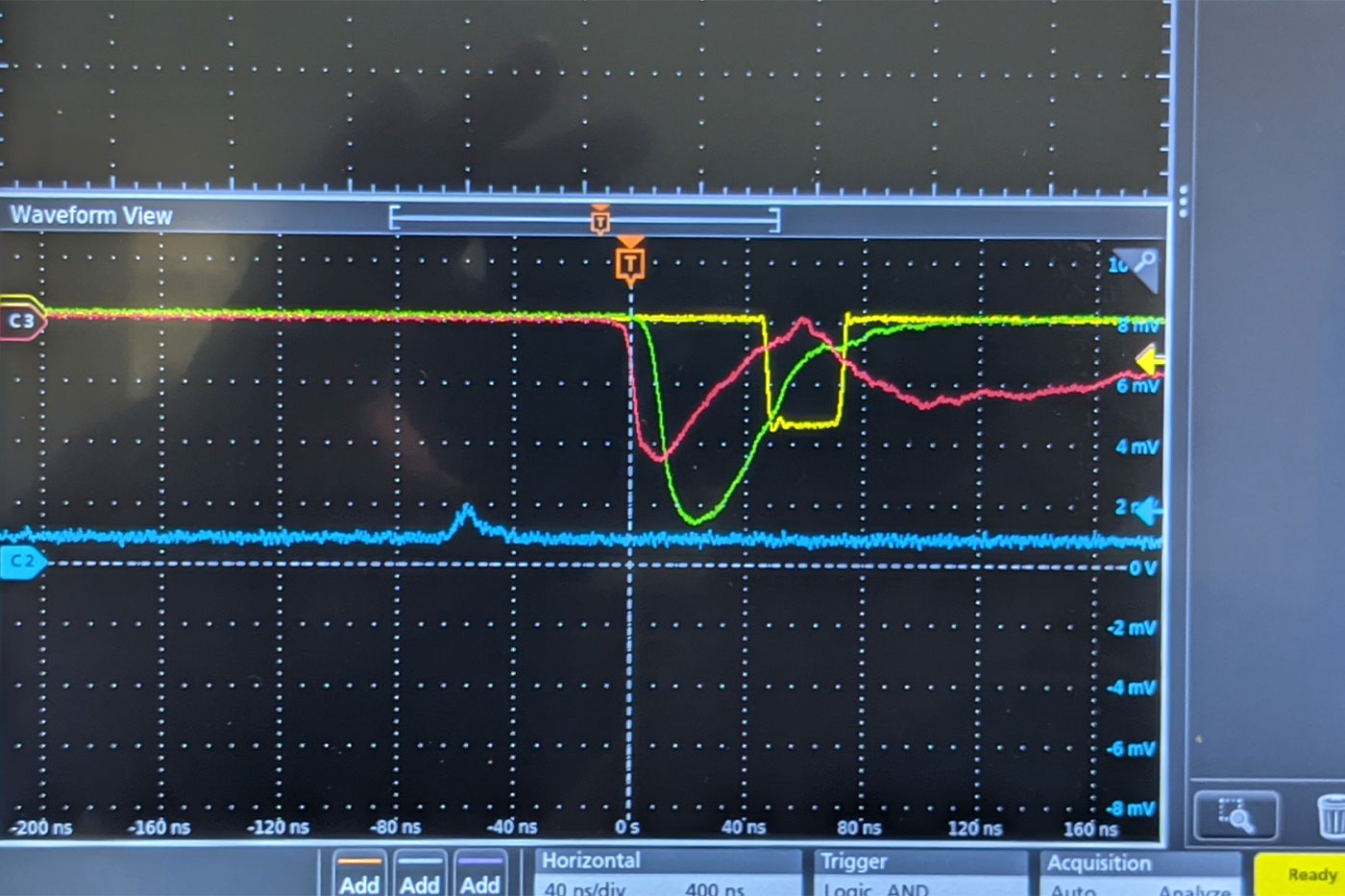

The four were part of a group of 11 student researchers from the university who developed and built a new type of particle detector, the HG-DREAM (High-granularity Dual-readout Calorimeter) prototype. The full team, including half a dozen faculty and support personnel, successfully conducted beam tests of the novel device at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Geneva, Switzerland, over nearly a month in the summer.

At the core of the project is better energy measurement of fundamental particles. When two particles collide, many smaller particles are seen in the experiment, and the energy measurement of these product particles – to the best possible precision – is important for future discoveries.

Texas Tech’s high-energy physics team is internationally recognized as leaders in the development and construction of calorimeters, which are a type of detector that measures the energies of fundamental particles from high-energy collisions. Building prototypes like the HG-DREAM has not been done before, and getting students practical experience with the science itself is vital for training future generations of particle physics scientists.

Nural Akchurin, a physics professor and one of the faculty members leading the detector project, is passionate about helping his students, who are the next generation of scientists. He was once that young student, needing guidance and an opportunity to get involved.

“I know how important mentorship is,” Akchurin said assuredly. “My professor did something like this for me when I was a kid. It stayed with me to this day. It made a difference.”

He himself was part of a team of Texas Tech researchers and other scientists whose work in 2012 led to the discovery of the Higgs Boson, or “God particle,” that gives fundamental particles mass – garnering a Nobel Prize for the larger team in 2013.

Akchurin says the next super collider is projected to be ready around 2045. Called the Future Circular Collider-electron positron collider (FCC-ee), it will most likely be built near CERN. He hopes some iteration of his team’s device will be implemented in the new collider; it would do an excellent job in measuring energies of particles and further the Higgs physics.

“There will be a bunch of experiments just like now, and one of the experiments that we are participating in would likely use this type of technology,” Akchurin explained.

He characterized particle physics as a contact sport, and students have to play the game, not just observe. They got the full experience through roughly 10- and 17-day journeys to the world-renowned lab on the border between Switzerland and France.

Caitlin Tidmore: From “Cosmos” to CERN

This second-year graduate student from Odessa, Texas, experienced her earliest science lessons with her grandfather over TV shows like “The Cosmos.” She studied chemistry and mathematics as an undergraduate, thinking she’d someday become a medical doctor.

“Then I realized I was no good around, you know, blood and whatnot,” she said, chuckling. “I was like, ‘Well, just that's not gonna work.’ I ended up just going the more chemistry-mathy route—research-wise, I had no clue what I wanted to do.”

The summer prior to entering Texas Tech, while still working on her undergraduate degree at Lubbock Christian University, Akchurin contacted Tidmore to see if she wanted to work around the APDL. She integrated herself there, making herself an essential part of that team. For her, going to graduate school for physics was new and exciting.

“I am fascinated with understanding and discovering the structure of our universe,” she said excitedly. “I started physically helping build the detector itself. And it snowballed into other things. Being in the high-energy program, they just wanted us to be there to see CERN, not only because we were grad students, but also because we could help. It was really cool.”

Tidmore admitted diving into research can be difficult, especially when one is first starting out.

“Don’t let that bog you down and think, ‘Oh, I don't want to do this because it's too hard,’” she said thoughtfully. “I think especially at Texas Tech, there are a lot of good resources, like your professors and students around you, who are interested in the same thing. As long as you make a community of people, anything's really possible if you’re particularly interested in it.”

Miles Harris: Average Student to Valuable Team Member

Just in his junior year, this professional physics major from the Dallas area knows he’s fortunate to have been one of only two students to travel on both summer CERN trips.

“As one of the tasks, Xander Delashaw, Caitlin and I plugged in a few hundred of certain kinds of cables,” Harris explained. “We had to keep track of where each cable was coming from on the detector and then into the readout system, as to not mix up the mapping for analysis. As a team we made sure things were where they were supposed to be, but working with sensitive electronics and hundreds of cables was definitely stressful.”

Harris is grateful for the preparation Texas Tech has given him to start well on the path to achieving his goal of working at CERN later in his career.

“It was definitely the help of the professors – them motivating me and me wanting their respect – because they’re such high figures in my life,” he said. “You have to kind of take charge of your own thing, and don’t be scared to give ideas. I mean, we’re undergrads talking to these professors who have Ph.D.s and these other postdocs. We’re trying to give them ideas on how to do things, and they're actually listening.”

He describes particle physics as a way of understanding the real world and how one can reflect themselves back into the universe through research.

“You’re studying yourself, just at a higher energy level because, I mean, the particles you’re studying at CERN, they’re no different than the particles that make up us,” Harris said matter-of-factly. “And I think that’s the most beautiful part of what we’re doing. There’s no difference between me and someone else or me and a coffee table, at the fundamental level, essentially.”

Valdis Slokenbergs: From Geneva to Geneva

This accomplished second-year doctoral student is no stranger to CERN or the field of particle physics.

“The funny thing is, even though I grew up probably 20 minutes from a national lab in particle physics as a kid, I had no interest growing up. Zero,” Slokenbergs laughed.

He earned his undergraduate degree at Johns Hopkins University, and he was fortunate to intern for three or so months at CERN one summer. The connections he made that summer eventually led him to Texas Tech.

Going back to CERN this past summer as a Red Raider, he and the second group of students spent an entire day completing the setup. Although, unlike the earlier group, his cohort did not have to unpack and assemble the three huge crates of electronics freshly shipped from Lubbock. Slokenbergs’ group spent five straight days on eight-hour shifts continuously collecting data.

He says this experiment will be central to his future career in physics. With the proposed new collider projected in the next 20 years, he and his fellow student-scientists are already becoming next-gen experts.

“You are the up-and-coming experts on how this thing works, why it works, and it gives you a reason to be part of this, to be in the room where it happens,” Slokenbergs said, his words accelerating as his excitement grew. “If you’re in the planning process from the start, and you’re young enough that in 20 years you’re still around in the field and you’re still active, all of a sudden, you’re very important and central to this project.”

Elizabeth Veraa: From Books and Questions to Readouts and Answers

The senior from Round Rock, Texas, is graduating in May 2026, with a double major in physics and mathematics. She started tackling those subjects in high school after she became hooked on stars and space in middle school.

“I used to struggle with math, but I learned that if you want to go do space things, you need some measure of math. Unfortunately,” Veraa said, with an expression somewhere between a smile and an eyeroll.

A couple of internships during the summers of her first two years at Texas Tech completely changed the trajectory of her studies from astrophysics to high-energy physics.

Coming into the APDL her junior year, she found a supportive research environment and the opportunity to travel to the world’s largest particle physics lab. Veraa has worked mostly on the software side of the project in the simulation area. For graduate school she wants to work on tasks that will lead to research on projects like the future FCC-ee. Having mentors she could ask questions of and help guide her has been invaluable.

“Working in the lab is a different kind of education that you can’t get in the classroom,” she observed. “I think that’s the best way to figure out if it’s something that you actually want to do, is by doing it.

“The experience helps develop your confidence that, ‘This is actually a thing I can do.’ Or maybe, ‘I don't know this now, but I can learn.’ And then especially a mentor’s approach of asking you, ‘What do you want to do? What do you want to work on here? What gets you excited? Let us help you.’ That makes it possible.”

From Lives Colliding to Companions in Research

Like protons circulating in a collider, the students who traveled to CERN were brought together for a high-stakes experiment that could be the very future of particle physics research.

The team of 11 student researchers also included postdoc Weijie Jin; graduate students Niramay Gagote, Akshat Shrivastava and Garath Vetters; and undergraduates Xander Delashaw, Harry Brittan and Michael O’Donnell.

Supporting Akchurin on the two trips were Mitchell Kelley, instructor in Electrical & Computer Engineering, and three physics faculty members: Christopher Madrid, assistant professor; Jordan Damgov, instructor; and Yongbin Feng, assistant professor.

Akchurin sounded like a doting parent when talking about the students’ determination, especially two of the undergraduates who were the only ones of the 11 to make both trips, connecting the separate teams and giving the installation and testing continuity. Delashaw and Harris were mission-critical, not just watching things happen but going about their assignments in a very serious way.

Harris recalled the stress of working with sensitive electronics and hundreds of cables. And how simply being there with the professors in their environment, being able to ask them questions and learn, eased the stress.

“I mean, we were in CERN, after all,” he said, breathing deeper as if to shake the anxiety and to moderate the excitement of the memory. “The world's hub for high-energy physics. A place where the professors we are working with have spent their lives, building and contributing to one of the largest detectors in the world. It is still kind of insane to think about even now. Overall, it was an experience I thought I would have to wait decades for. I am extremely thankful to all the professors at the lab, and to be given the responsibility I and the rest of us students were given.”

Slokenbergs firmly believes that at Texas Tech, he’s in the right place, doing the right things with the right people, resources and energy to make it possible.

“It's hard to create excitement – or energy – without the other two things, mentorship and resources,” he said with certainty. “That’s what I’ve found here that really sticks out to me, is it’s the combination of those three that I really enjoy.”

Summing up what he knows from his decades of experience, Akchurin circles back to two fundamental elements of science and students colliding together.

“You know, nature is kind of funny this way. Nature likes to keep its secrets,” Akchurin said with a mischievous grin. “As a student, when you start seeing how you might want to take a peek – you know, learn something – that's a huge experience for them. It was for me when I was a kid; it was great. Somebody did this for me, so we’re making it possible for these students.”