The School of Law is serving rural Texans through its public defense office and clinic.

(Header photo: Courtesy of Texas Tribune)

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to legal representation in criminal prosecutions. It’s a right that sets America and its citizens apart.

When someone cannot afford legal representation, it’s usually provided by the state.

Texas has placed that responsibility on individual counties.

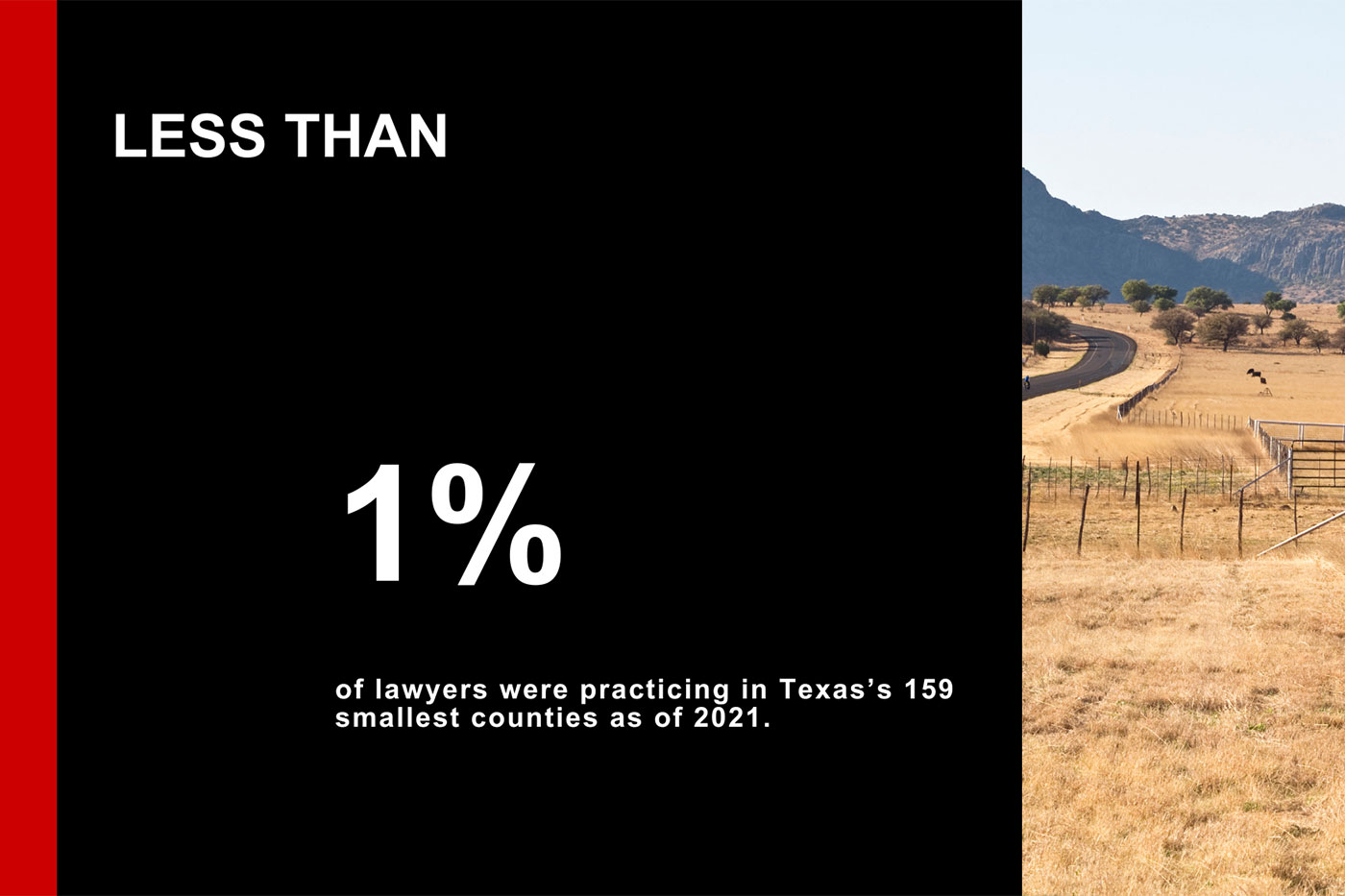

In rural areas, that can strain the county’s budget and leave defendants with delayed or absent representation altogether. It’s a struggle to meet this need. There are simply far more people needing representation than there are lawyers.

In 2011, Texas Tech University’s School of Law realized it had the resources to help alleviate this dilemma while, simultaneously, enhancing its students’ educational experience.

The Caprock Regional Public Defender Office and Clinic serves more than 10 West Texas counties by representing defendants in criminal cases who would otherwise be unable to afford it. By providing legal counsel and advocating for their clients, students participating in this clinic finish law school with hands-on experience that lands them competitive positions.

The clinic just concluded its 14th year serving the people of West Texas under a new chief public defender, Joe Stephens.

“How do we help this population who needs lawyers but are just sitting in jail?” Stephens posited.

He argues the solution to this challenge is educating individuals on their right to representation but also getting more lawyers to move to rural areas.

“The only reason some people sit in jail longer than others is because they don't have money,” he says. “One of the things about indigent defense that I think is critical, is making sure people get the same quality, if not higher quality, representation although they don’t have money. It’s the joy of my work.”

That joy spread to the three students in his clinic this past year: José Covarrubias, Victor Lopez and Ethan Jimenez.

“Joe is the best professor I’ve ever had,” Victor said.

Anything Could Happen

It’s a warm Monday in late April. José, Victor and Ethan pile into Joe’s white sedan and begin their drive from Texas Tech’s School of Law out to Plains, Texas, population 1,300.

It’s about an hour drive, so there are no stops. On longer drives, the group will stop at an Allsup’s Convenience Store for snacks – a pastime in West Texas as ubiquitous as Friday night football.

In the car, Ethan is the external processor of the bunch.

“I gab a lot,” he admits.

José is quiet, but his mind is moving quickly. You can tell by his furrowed brow and the way he leans toward someone when they’re talking. José has closed more than 35 cases this year and has worked on more than 70 – a feat for any third-year law student.

They’re headed to the Yoakum County Courthouse today to handle a few misdemeanor cases on the docket, and a contested hearing.

“In this specific hearing, the prosecution hasn’t turned over the evidence they want to use in their argument,” Stephens says. “Because of this, José is requesting the judge exclude the evidence if we go to trial.”

As the students arrive at the courthouse, they’re greeted by a member of the sheriff’s department who lights up when she sees the Texas Tech professor and students.

“I hope you didn’t come wearing your sassy pants today,” she teases.

The environment is palpably easygoing. But that doesn’t mean the law is any less important. As the students enter the courtroom, County Judge Michael Ybarra enters the chamber and the 16 individuals awaiting decisions from today’s docket stand.

Before any cases can be heard, though, District Attorney Paul Mansur motions to Professor Stephens and José for a sidebar. No one in the courtroom can hear what’s being said, but the three men stand in a circle, hands gesturing wildly.

As they file back in, Mansur indicates to Judge Ybarra there has been a last-minute development affecting the contested hearing.

The environment has lost its easygoing feel, taking on a solemn tone.

“It’s my duty to inform the court that on Friday, the Denver City Police Department terminated one of their employees who’d been responsible for cataloging evidence,” Mansur reports.

As the district attorney and Professor Stephens’ group went back and forth, it became clear that not only would this development make evidence in today’s case inadmissible, but it would have ramifications dating back years.

Evidence had not been properly cataloged since 2018.

“This situation is an outlier, but it’s not surprising,” José says.

Victor and Ethan agreed it’s moments like these that prepare them for real-world practice.

“When you walk into court, anything could happen,” Stephens adds. “What happened here today is a perfect example of that.”

And Stephens would know best. His decades of experience have primed him for the unthinkable.

With a Bachelor of Art in International Public Policy from Vanderbilt University and a Juris Doctorate from the University of Texas, Stephens launched the Concho Valley Public Defender’s Office in 2021, establishing service in central Texas that served 12 counties’ indigent cases.

Stephens was trained by Justin Brown of Brown Law in Baltimore. And if that name doesn’t ring a bell, one of his clients’ might – Adnan Syed, the subject of the investigative journalism podcast “Serial.”

A Story’s Scope

Stephens journey to public defense was far from linear. He was born in Melbourne, Australia but when his father was reassigned to The Age’s D.C. desk, the family moved to the United States.

“The things important in D.C. weren’t important to me,” Stephens remembered.

This might be surprising coming from someone who studied international public policy and became a lawyer, but Stephens’ ambitions weren’t so black and white. Storytelling was at the center of his upbringing.

So much so that he has a tattoo of Winnie-the-Pooh on his right arm.

“Everything in the world lives in that book,” he said. “Any lesson you want to learn is in those stories. Those characters gave me permission to be vulnerable.”

A vulnerable guy with a cartoon tattoo hardly fits the stereotypical image most people conjure up when they hear the word lawyer. Many surprising characters colored Stephens’ childhood: from his friends in the Hundred Acre Woods to Sherlock Holmes to Atticus Finch and Boo Radley.

Young Stephens was infused with a hunger for learning, and he still hasn’t been satiated. When he decided to practice law, it was a matter of finding a balance between logic and passion.

“Storytelling is a collision of different ideas, and when you can use it to bring life into the courtroom, I think that’s so powerful,” he said.

Stephens traces his success in the courtroom with his appreciation for stories. He insists great lawyers are skilled listeners. They’re good at asking questions. They hear and understand what someone is saying and can pivot their line of questioning at a moment’s notice.

Which is exactly what happened at the Yoakum County Courthouse that day.

Showing Up

“When you’re put under pressure you either fold or you grow, and for us it’s been the latter,” Ethan says.

When cases change as rapidly as they did on that day, it engages a different part of the students’ brains. They cannot prepare like they can for a test, ruminating for days and reviewing material. They must recall information instantly, communicate clearly and stay focused on what’s fair for all involved.

With the exclusion of evidence, José was able to help his client avoid separation from his family and superfluous, added charges.

In many of the cases the students work, outcomes are rarely a simple not guilt or guilty verdict.

“We’re looking at what’s most appropriate,” Victor says. “That’s different in every case.”

Public defense work is not for those who live by cut-and-dry answers.

“Some of the clients we defend in our clinic probably are guilty and did what they’re being charged with,” José says. “But the Sixth Amendment means everyone gets representation, and they get a fair trial. Most defendants are not monsters. They’re human beings.”

After court adjourned for the day, José, Ethan and Victor go over other open cases with Mansur. For over an hour, they go back and forth on the minutiae of charges, possible charges and argue what is fair for each, unique case.

Ethan discusses a client who is being grouped with another defendant.

“You charged two people with the same felony offense because they were in the same car while pulled over. Now during negotiations, you won’t treat them as separate cases?” he asked the DA for clarity. “With all due respect, these two individuals need to be seen as that, individuals.”

Mansur told Ethan he wasn’t willing to change the charges at that point but would keep the details introduced in mind.

Stephens nudges his student as they walk out of the courthouse.

“Really great job in there Ethan,” Stephens affirms, “you didn’t let up.”

They talk through the case on the ride home.

“I was disappointed I wasn’t able to convince the prosecutor to dismiss my client’s felony,” Ethan says. “On the other hand, I feel confident I’ve completed all the work and exposed all the holes in the state’s case.”

Ethan says the opportunity to sit down with prosecutors in real time about real cases is monumental. Often, clinical students must speak with prosecutors over the phone or through email. When a sit-down occurs, that’s where the real work gets done and negotiation skills are on full display.

In-person meetings can also move cases along at a quicker pace.

“Those interactions are always better than discussing a resolution over the phone,” José added. “Without that presence, it’s easier for prosecutors to avoid reaching a decision.”

And the longer a case goes unresolved, the more real-world implications their clients face.

“A client might have a job offer but with a criminal case looming, the client cannot progress in life,” José said. “Sometimes bond conditions are so restrictive they’re unable to see their own children until the case has concluded.”

But even when they don’t get the ruling they hope for, Stephens’ students are taught showing up and listening is paramount.

“You lose when people become just a number,” Stephens says.

In some cases, the students are the only ones going to bat for defendants; the only ones who listen to their story; the only ones who are willing to embrace the gray areas.

And for Stephens, that’s where the law becomes fascinating.

Calling Him Back

“My relationship with my law degree has always been a complicated one,” Stephens mentioned.

After finishing law school in Austin, Stephens worked at a civil firm.

“I hated it tremendously,” he asserted.

He longed to do something that felt more personal. Needing a reprieve, Stephens moved to New York City and was on the opening team of two restaurants in Manhattan. He enjoyed how “serving” people came with a positive connotation, for a change.

He loved creating a sense of belonging and ambiance. There was deep gratification by placing a meal in front of someone, cooked to perfection in a matter of minutes, after dealing with legal cases that could drag on for months.

“I think that’s why I love food, and I love cooking,” Stephens said. “You get this relatively quick sense of completion.”

But try as he might, Stephens couldn’t push the legal system out of his mind. Many of the people staffing kitchens were coming out of prison. Everywhere he turned, it felt like the law was calling Stephens back.

In 2018, he began working with Brown Law in Baltimore. This was a few years after Adnan Syed had become a household name through “Serial.” Stephens’ involvement in the firm, however, was mostly in appeals – not in the cases themselves. He was reading the stories after they’d been written. He yearned to have a stake in the telling.

“I learned I didn’t want to read about how others did their job,” Stephens said.

Then Stephens met a man named Lloyd Hall. It was one of the few cases he was involved in during his time in Baltimore that opened his eyes to a part of the law that consumed him.

Hall had been serving a life sentence for 34 years when Brown was able to overturn the ruling and walk him out of prison.

“I didn’t do anything on that case,” Stephens said. “This was years of work that predated me. But being there and seeing that result was amazing.”

Stephens wondered how many people might be serving prison time, who, in fact, were not guilty. People who hadn’t been given fair representation, or any representation. As he researched indigent populations, he realized that oftentimes socioeconomic factors directly factored into an individual’s legal experience.

The man who grew up reading about the compassionate Atticus Finch found his way to the work of public defense.

Meeting the Need

“I have no interest in being another kind of lawyer, zero interest. But it’s exhausting, difficult, chaotic work. I liken public defender years to dog years,” Stephens jokes.

The professor says the workload his three students took on this past year is insane. But they’re inspired by their teacher.

“Being around Joe just makes you want to be a better person,” Ethan says.

Stephens has certainly left an impression on the three young men, all of whom just graduated from the School of Law.

José will work for a district attorney’s office, Ethan has a position lined up on the defense side but this time for a large corporation, and Victor is still oscillating between a few options.

While their jobs might be different from the perspective they’ve had in public defense, they’re hopeful to gain well-rounded experience and get different kinds of practice under their belt.

Two of the three are open to working in a rural setting in the future.

Judge Ybarra, who presided over the hearings in Yoakum County, says the clinic and its students help his courtroom run smoothly.

“It’s my statutory requirement to ensure the defendants understand their rights to have access to qualified professional legal representation and consultation,” he says.

Judge Ybarra says he’s seen many defendants feel they can handle the complex legal process on their own. This is a decision that causes him some apprehension.

On the day the students were at the courthouse, Judge Ybarra assigned a new client to them. An older man appeared for arraignment and had no consistent work. What he could get was strenuous physical labor.

The man had severe burns across his body and had undergone multiple heart procedures, making it incredibly unlikely he’d be able to work enough to cover the costs of legal representation.

“Let’s get him assigned to Caprock,” Ybarra says to his staff.

“Caprock Regional Public Defense Office is a vital component of the success of Yoakum County Judicial Court,” Ybarra explains. “Like many rural counties, finding adequate representation for indigent defendants is often difficult. Caprock has done an outstanding job filling that gap.”

The judge also said working with law students brings a fresh energy to the courtroom.

“I enjoy seeing the enthusiasm and confidence portrayed by the student attorneys,” he says. “For students, this is often the first time the classroom meets the courtroom.”

José, Victor and Ethan agree that spending a year in the clinic has changed them for the better. While they hope they’ve made a difference for the people of West Texas, they know they’ll carry the stories with them wherever they go.

“When I hear ‘From Here It’s Possible™’ I think about where I started and where I am now,” Ethan says. “My dream of practicing law started when I was a young boy at my grandmother’s house on the south side of Odessa, Texas.

“Many years later now having done so, I think about all the great opportunities Texas Tech has given me along the way – the Caprock Regional Public Defenders Clinic being the greatest one of all. Truly, at Texas Tech School of Law anything is possible, especially with great faculty like Professor Stephens.”

And while these three students have graduated, the clinic’s work is far from over.

Stephens is already busy reviewing applications for the fall. With his first year under his belt, he’s looking to take on a larger number of students this time around. There is certainly enough work to keep them busy.

Perhaps, through programs like this one, there will one day be enough representation in rural Texas to meet the need.

The Caprock Regional Public Defenders Clinic is one of eight clinics offered to third-year students who meet certain requirements at Texas Tech. Fulltime faculty members with extensive trial experience at both state and federal levels oversee the clinical courses. For more information, visit the clinical programs website.