Annelise Nguyen has stashes of Legos and Mini Coopers, but it’s the contents of her laboratory that are helping make a difference for both animals and humans alike.

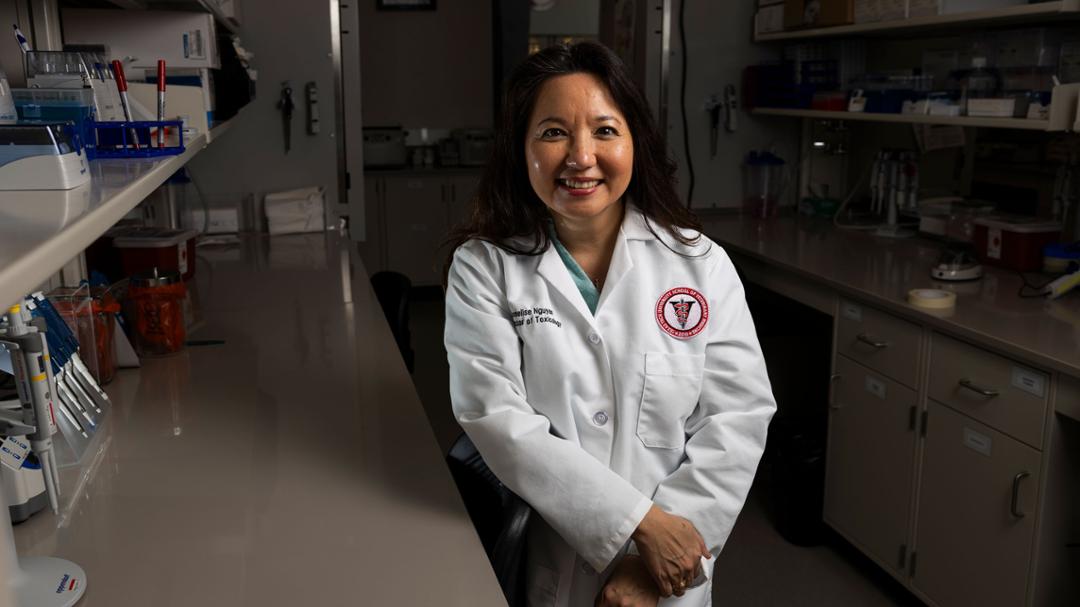

If there’s a miniature Mini Cooper zipping down the hallways of Texas Tech University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, there’s no doubt Thu Annelise Nguyen holds the controller. She’s just keeping the pep in her step as the associate dean for research and a professor of toxicology.

The motorized toy is one of many models of her favorite vehicle featured in her office that brings her own personal flair to the room, brightening it in the process. The door remains open and inviting to the plethora of young minds and colleagues who seek out her expertise and mentorship on a weekly basis.

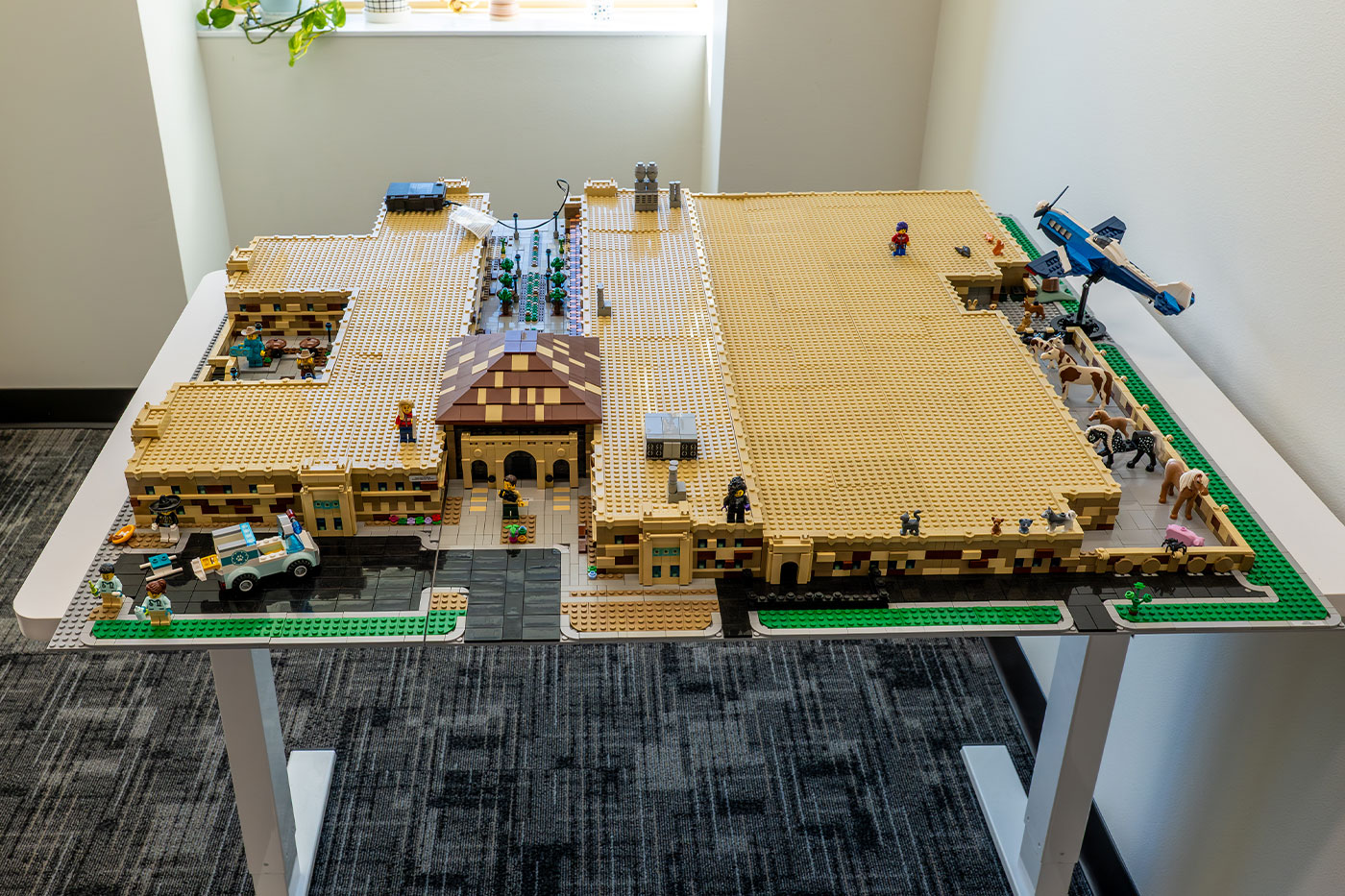

Also featured are an assortment of vibrant Lego assemblies – mainly bouquet arrangements – but none near as complex as the structure just outside in the hallway.

Using the miniature blocks and her gift for engineering, her initial major in college, Annelise constructed a to-scale replica of the School of Veterinary Medicine building with such fine attention to detail that students, faculty, staff and plenty of animals are featured throughout the hallways, rooms and foyers.

She did this not only as a pastime, but to reference during frequent community tours she leads. It’s an extra initiative for the cancer researcher, but Annelise is determined not to let the white lab coat she wears cloak who she is and what she does.

“Biology is a lot of memorization, but engineering is so deep and I just love it,” she explained of her skillsets. “I analyze three dimensionally and that’s a skill needed in this challenging world that not everyone has. So, I continue down the path with my engineering mind, and that’s why I think I advance so well in toxicology.”

Annelise is all smiles on the outside but is tenacious when it comes to seeking out vulnerabilities within cancer cells as proven by her early career work at Kansas State University. Starting in 2001, she dedicated 10 years to understanding unique traits of breast cancer cells so she could design anti-cancer drugs. She patented the molecules she formed alongside a chemist and sold them commercially, working with her students each step of the way.

“I am constantly thinking about unmet needs and trying to solve a problem, so I try to influence my students with that energy and love for science,” she said. “Some of them have never had anyone motivate them to go beyond understanding how an organism works to think about its place in society.”

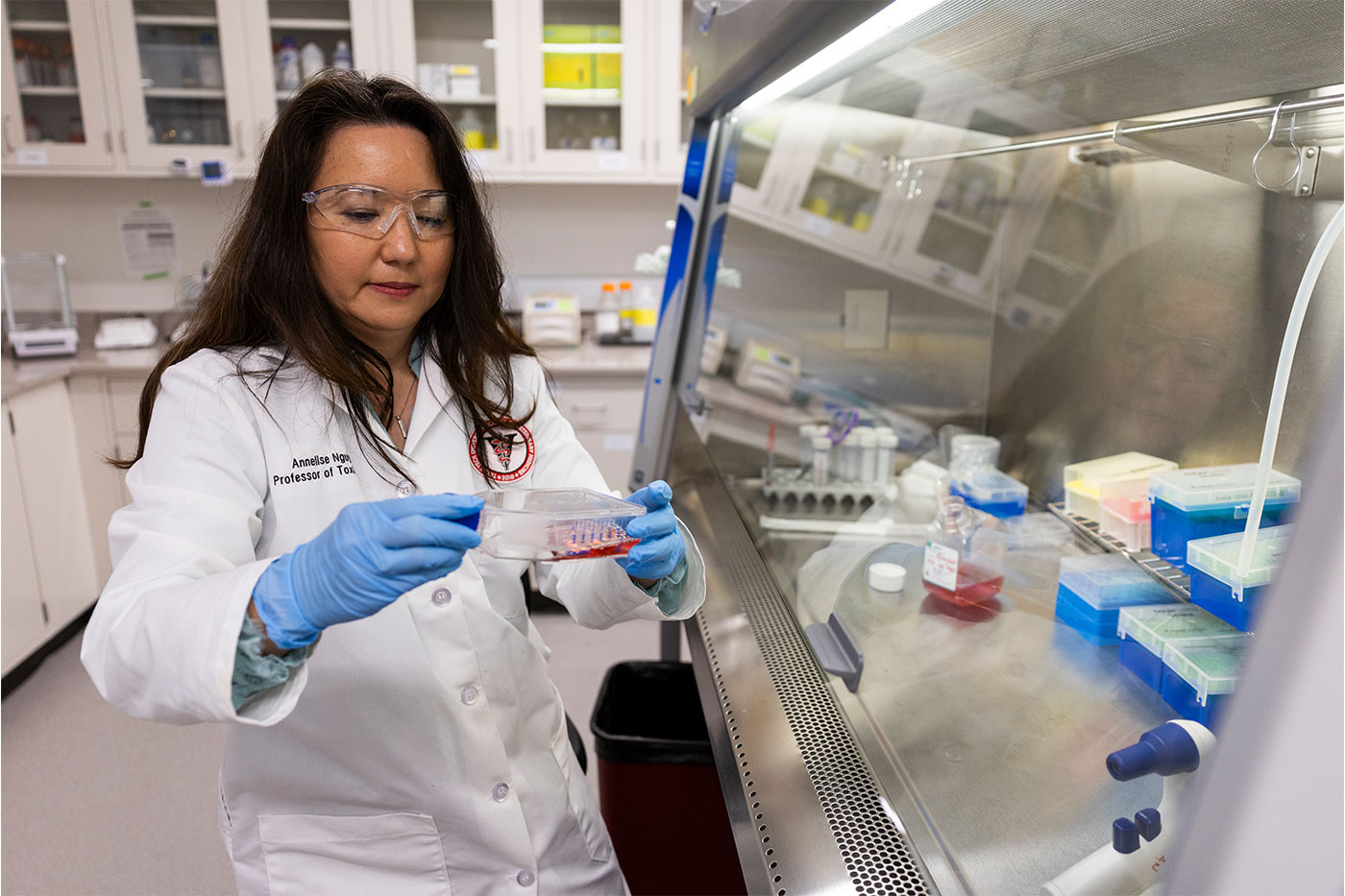

Her next venture started in 2015, when Annelise began to prioritize precision medicine and developed ex-vivo tumor organoids to evaluate anticancer drugs. This required her to recreate a tumor outside of the body that would undergo tests so the patient could learn the most effective treatment option for them. That technology is also patented and commercially available.

Afterwards, Annelise considered a switch from academia to climbing the ranks of the corporate ladder. She pursued this route and received offers for director positions with Boehringer Ingelheim and the National Cancer Institute.

“It was truly a moment where I had to consider giving up the whole career of being trained and nurtured to be a professor,” she recalled. “The students would disappear once I signed that contract.”

But then she began to be recruited by Texas Tech’s School of Veterinary Medicine in 2020 – offering her a chance to further engage with pupils.

It would mean a big move for Annelise and her husband Michael Tran, a podiatrist with a private practice for 20 years. They both started as engineering majors at Texas A&M University before switching into the field of biology, pouring their energy into helping others.

In Annelise’s case, the students she has mentored have felt like her own kids in a way as she has aided in their growth and development.

“I’m so excited and am a cheerleader for them,” she said. “Not everyone has that kind of personality because they have their own kids and they can only devote a certain number of hours to their job. I don’t see this as an 8-to-5 kind of job, but part of my life.”

The couple determined that returning to their home state where she understands students’ educational backgrounds would just make sense. Even though joining Texas Tech would require leaving a stable job to help build a program from the ground level, there was a draw in comparison to her corporate offers: she felt not only valued but truly needed by the School of Veterinary Medicine.

“Five years ago when Annelise told us she would join our new program, we knew she would contribute something truly special to our school and to all of Texas Tech,” said School of Veterinary Medicine Dean Guy H. Loneragan. “But it turned out we got something far more special. Annelise has been transformative, inspirational, and above all else, someone who is able to achieve great things.”

Ode to Obi

The most exciting aspect of Annelise’s new gig would be transitioning what she learned with human research to veterinary medicine. Her first project was personal, involving a furry family member named Obi-Wan Kenobi.

This fluffy feline went everywhere with Annelise and Michael, curled up behind the driver’s seat of their car. His happy-go-lucky nature somehow mimicked Annelise’s own personality as he seized each day, whether that was by going full Godzilla mode on her latest Lego cities or curling up in a suitcase to ensure he made the trip.

So, it was rather alarming when Obi-Wan wouldn’t come out from underneath the bed. Not even dinner or his favorite laser light were effective lures.

He was crying out in pain, and an X-ray confirmed why.

“He had tumors all over, from the kidneys to everywhere,” Annelise recounted. “It had metastasized all over.”

It was too late to save Obi-Wan. Annelise and Michael had to say goodbye to the shelter cat rescue turned precious pet after more than seven years.

As a cancer scientist, Annelise was positioned to help cats suffering from similar conditions knowing this entire species is prone to kidney disease. She collected samples of Obi-Wan’s tumors and moved them with her to Amarillo.

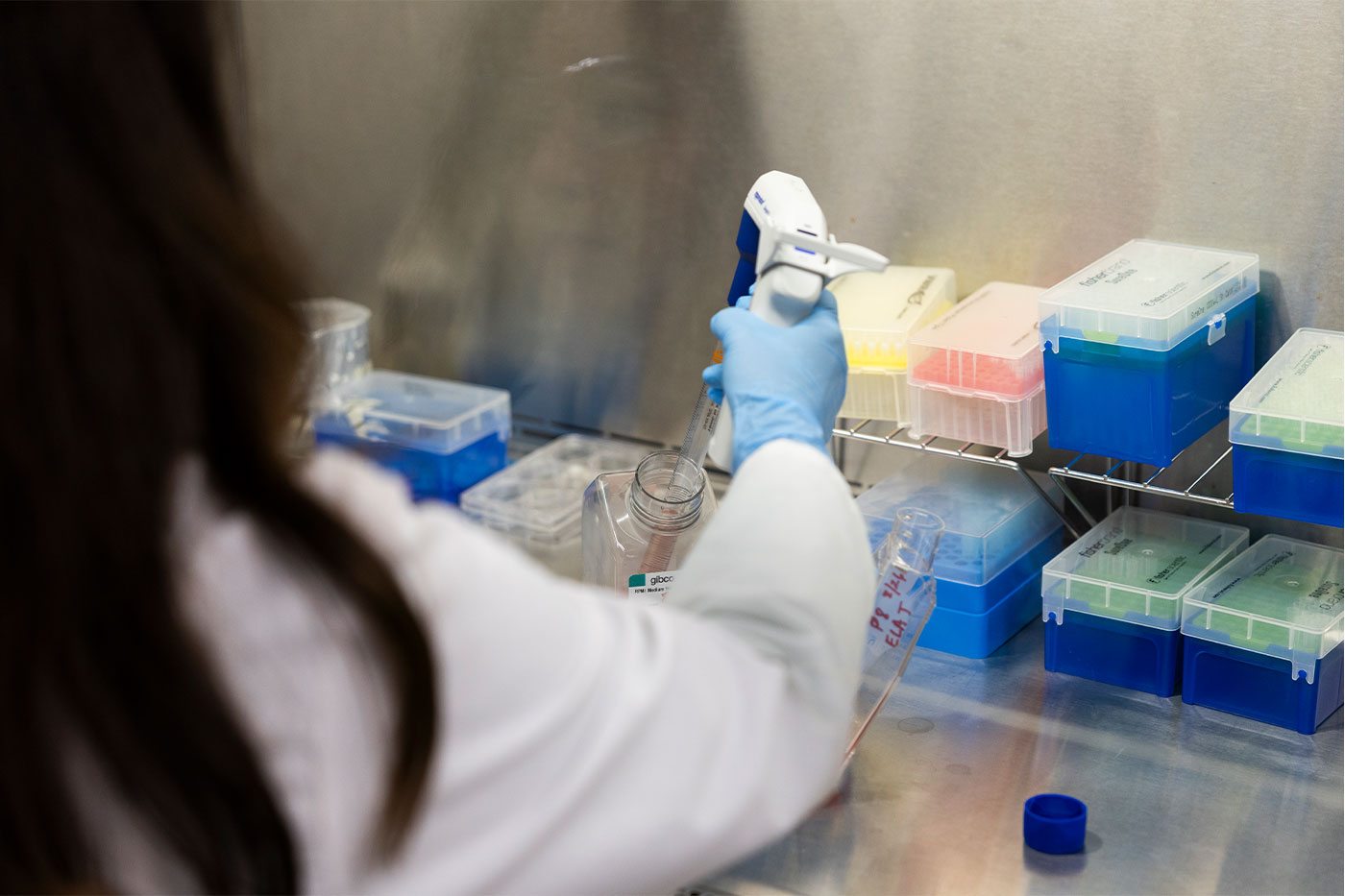

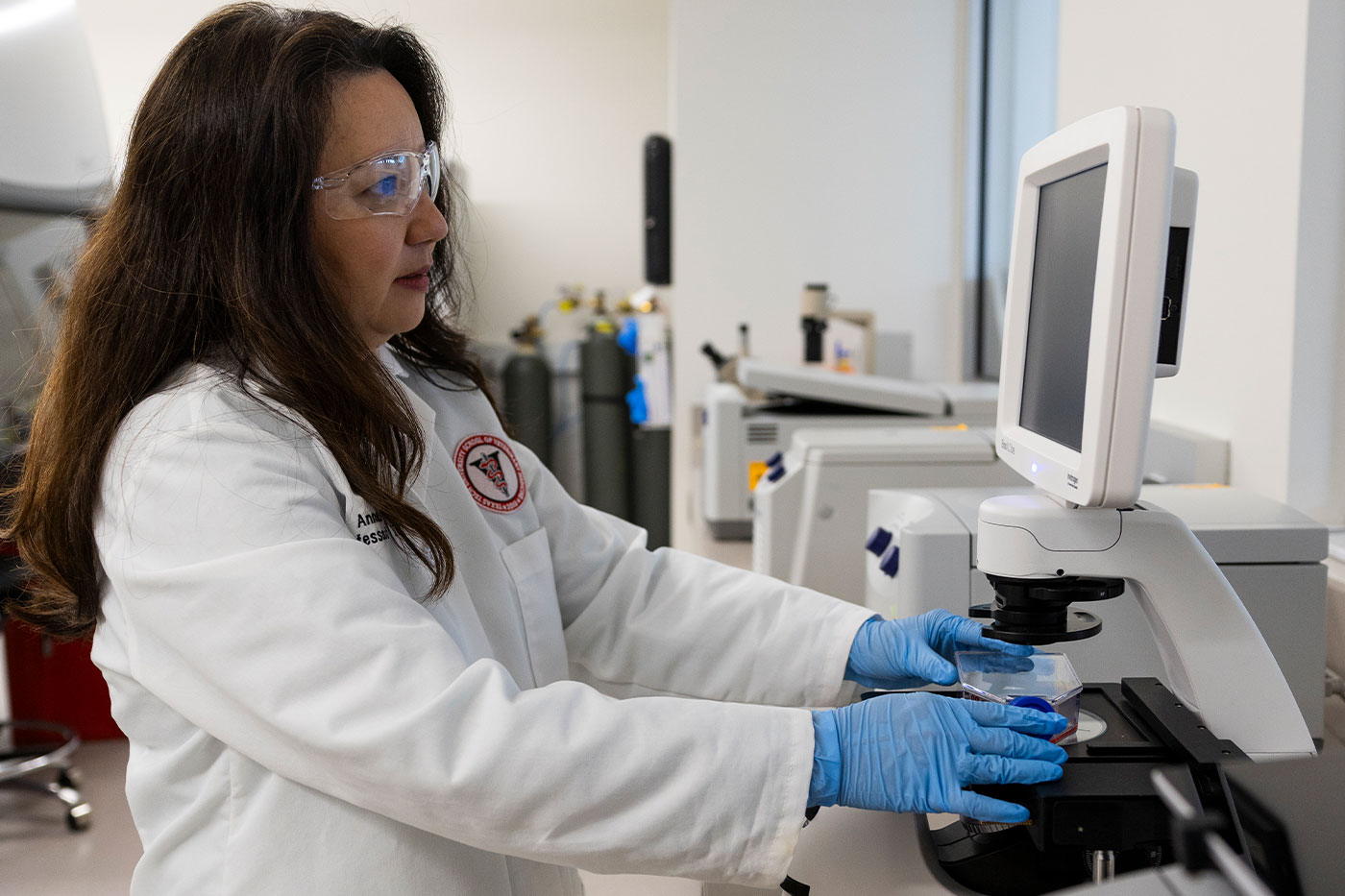

In her new lab space in the School of Veterinary Medicine, she isolated the first feline kidney carcinoma cells in the world.

“It happened to be in our hands, so I thought, ‘Let’s do something about it,’” Annelise said of the feat.

This was an anomaly because typically by the time cancer-stricken and diseased pets reach researchers they are already degraded or have received rounds of chemotherapy drugs that have killed the live cancer cells.

Annelise took her rare findings to the Innovation Hub at Research Park to gain support needed to make the cell line become commercially available. In an ode to Obi-Wan, she named them “Obi cells.”

Researchers who access Obi cells can use them to perform tests and determine answers about the disease. As for herself, Annelise has purchased anti-cancer drugs to see which treatment effectively stops the cancer cell growth – an option she wishes could’ve saved sweet Obi.

“We have plenty of drugs out there, so I’m just going to refurbish those drugs for a cat cancer,” she said. “If I can find a vulnerability or specific signal just for cancer, then I can design a drug that is targeting that population and not normal cells.”

This is an example of how Annelise invites students to think critically outside of the classroom, pushing the School of Veterinary Medicine’s teaching mission to not only educate but discover.

“We are not doing our students any good if we don’t provide them with opportunities,” she noted. “We can produce great veterinarians, hands down, but a few of them want to exceed beyond being a vet at a local clinic, and if we don’t invest in those small populations, then we are behind. So that’s what I’m doing, and that was my task on day one.”

Revitalizing Research

Annelise channeled her work ethic to compile research opportunities for students before they were even enrolled her first year with the School of Veterinary Medicine. This required calls to several local veterinary clinics.

“I told the clinics, ‘If you have patients coming in and the owner decides not to do chemotherapy and does a surgery removal, then call me. I can be at your clinic in 30 minutes,’” she said.

The cancer scientist received many of these calls and collected samples she stored in her laboratory. To date she has about 100 human and animal cell lines she refers to as “tools” in her freezer room.

In addition to applying her comparative medicine knowledge to feline work she can offer with Obi cells, Annelise applied her breast cancer findings to canine mammary tumors in search of more effective drug options that can attack cancer cells when there are no estrogen receptors to target.

Another opportunity with canine research presented itself last year following one of the professor’s toxicology lessons. One of her students, who is interested in orthopedic small animal surgery, visited her during office hours to ask if she had a project that would help him become more competitive for a residency program.

When she asked what the student was specifically interested in, he said osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer his veterinarian father frequently treats in dog and cat patients. Annelise lit up even more than usual, because she just so happened to have a sample of canine osteosarcoma that she invited him to test with the anticancer drugs she purchased for her Obi cells project.

“I just love when a student comes to me and has a specific thing they’re excited about, so the energy is already there,” she shared. “His mentor is really excited that they have a student who went off to the Texas Tech School of Veterinary Medicine who is going to be involved in a project that might have drug discovery that will eventually feed back into the clinic. That’s why I think I brought along invaluable resources that added to the Texas Tech portfolio.”

Leadership within the School of Veterinary Medicine noticed how important Annelise’s contributions were – and fast. Just one year after her arrival, the research and innovation enterprise needed a leader and a national search commenced.

But they didn’t have to look far. The ideal candidate was there all along: Annelise. This role would require her to support and promote research, scholarship and creative activities for faculty and students while still maintaining and contributing to the school’s research portfolio in cancer research.

Annelise began to channel her “Martha Stewart” lab organization skills to form layouts and systems that allows researchers to work smarter, not harder. The labs were even designed with windows to open researchers to the occasional passerby and potential engagement opportunities.

“I spend most of my time with faculty,” she explained of the role change. “I manage how they conduct research, assign research labs and get all the research dollars they need to maintain their equipment. Helping them is what keeps me up at night.”

Organizing One Health

Annelise would get more chances for student interactions as she was tasked to create the One Health Sciences doctoral program due to her deep understanding of how research can benefit human, animal and ecosystem health interconnectedly. This degree needed to align with the current demand for an interdisciplinary and interprofessional approach to improve public health on not just a local but global level, which required a lot of homework for Annelise.

“That is not my expertise – I’m a cancer researcher,” she exclaimed. “But I think that I’m the right person to make things happen, so I was excited to do that.”

Once the program was assembled and approved, Annelise had to sell her creation to graduates based on trust alone. She was able to get 25 students to commit by emphasizing while the program was new, the faculty involved packed impressive backgrounds and experiences.

“I was able to stay with the program to make sure that the students settled,” she said. “I felt like I needed to not only play a role in implementation but also stability.”

Fourth-year One Health Sciences doctoral student Tomas Lugo was one of those who not only believed Annelise but also wanted to work with her.

Tomas is a three-time Texas Tech student and the first of his family to attend college. He earned a bachelor’s in biology with a minor in chemistry and then attended the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and earned a molecular pathology degree.

He was already working in medical centers but decided he wanted to pursue more research opportunities that would integrate human and animal medicine. Annelise’s offer was the perfect match for his ambitions.

Before Tomas joined her lab work, she dedicated two weeks to training him from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., a commitment she has learned empowers her students.

“Once I teach them all the tools they need for their project, then they are independent,” she shared. “They go from understanding why we do the way we do it to asking the critical questions for the project.”

Through the use of Annelise’s ex-vivo tumor organoids, the duo began to use the technology to see if they could provide individualized precision medicine for colorectal cancer by partnering with BSA Harrington Cancer Center in Amarillo.

This gave Tomas the unique opportunity to provide hope to patients as they undergo cancer treatment; that one day they may not have to be the guinea pig of trial and error.

“Dr. Annelise is a really great mentor,” he commends. “She helps me understand the nuance of research and is also very stringent on how to do things, which has helped me become a better scientist. One of the big things she always tells me is to try the opportunity, and even if you fail, there’s something to learn from it.”

Tomas also observed how Annelise seizes the moment as she collected a sample from a horse who was taken to the School of Veterinary Medicine after it died from an autoimmune disease.

She took it directly upstairs to her laboratory, where she was able to propagate live cells and grow them. When she checked, just like in the case of Obi-Wan, there appeared to be no cell lines of this kind in the commercial directory. She and Tomas ensured that changed, and researchers can now access the cells through Applied Biological Materials.

“It was very cool to see my hard work actually produce a product to help further the field,” Tomas remembered.

Annelise encouraged Tomas to take the science even further by comparing the genomic DNA of the diseased horse to that of a healthy one. The data uncovered by the sequencing revealed thousands of mutations that could be traced to discover the cause of the disease, which could then be tested for a treatment option. She would then see about applying those findings to human autoimmune diseases.

The potential of this project spread rapidly through the halls of the School of Veterinary Medicine.

“Students knock on my door and ask, ‘Can I work for you on this project?’” Annelise said. “Their horse on their ranch might have this disease as well, and now they can learn about it from the molecular cell level.”

The payoff of involvement in Annelise’s laboratory is a strong resume, which has enabled Tomas to weigh job offers that include a position with MD Anderson Cancer Center (where he hopes to be a principal scientist one day). The rest of his inaugural One Health Science classmates also have secured job offers, proving their blind trust in Annelise’s new program was well worth the risk.

She even exceeded expectations on her other task to establish the school’s research and innovation by creating student experiences beyond the classroom.

“In addition to her own research, discovery and intellectual property advances, Annelise has established a vibrant research enterprise at the school and brings together graduate students, professional veterinary staff and faculty to do great things,” Loneragan said. “Her contributions are extraordinary and will leave a lasting impact on our school and across Texas Tech and beyond.”

Annelise has seen firsthand how her role is impacting the future of academia by keeping in close contact with her former students at various conferences and online.

“It’s funny – my mentors and students have their own students they will send to me,” she said. “So, it’s like a different generation. Only in academia do we have that opportunity to see students’ connections.”

She keeps this in mind as a supervisor, creating a high standard in which students can gauge their careers, or an example for them to follow as they lead their own laboratories.

Many of Annelise’s former students don’t realize her positive reinforcement methods have spoiled them until their next role.

“They call me back and tell me they have a different type of boss or supervisor who is disoriented or not appreciative or understanding,” she said. “I’m so glad I exposed them to an environment that they’ll have to adjust and look for something that matches their expectations.”

Annelise has sat in their seats before and knows how vital mentorship and building credentials are, along with accountability. This is why she is so open to sharing her experience and research projects with her colleagues and students.

She does this all with a smile from her corner office – the secret to happiness not just Lego art or decompression laps with a motorized Mini Cooper, but the satisfaction of meeting a purpose.

“I think that’s where my personality comes from; I’m getting paid to do something that I love and it’s a blessing,” she stated. “I never imagined I’d be where I am right now.”