Life had other plans when Jovani Armendariz wanted to be a veterinarian. But through wearing many hats, he will earn his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from Texas Tech this May.

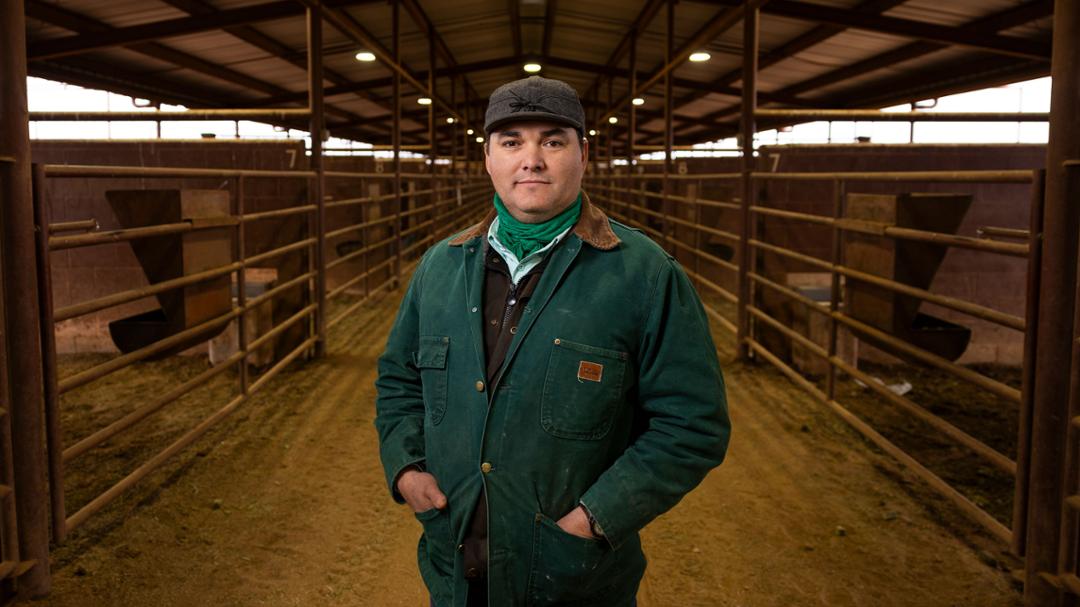

Jovani Armendariz pulls the earband of his wool cap to shield his ears from a frigid bite as he passes through rows of dairy cattle.

The hat permits the flexibility required of this Texas Tech University School of Veterinary Medicine student during his fourth-year clinical rotations at veterinary practices across Texas and New Mexico. During this immersive experience, he could find himself anywhere from being indoors performing an ultrasound or tooth extraction to on the road for “farm calls,” checking on horses experiencing symptoms like lameness – or worse.

This is part of following in the footsteps of veterinarians he aspires to be like during the hustle of their workday, shadowing their every move to determine their ethics and methods.

“I told the doctors at this last practice I felt like my biggest goal while being there, aside from learning, was not to get in their way through such a busy practice,” he joked.

But despite walking this careful line, Jovani maintains a spring in his step knowing he could bear this workload in mere months, once he earns the degree that will change life for him, his family and – even more – his community.

It took nearly four decades to reach this point, and none that he would skip. Looking back at those years like pegs on a rack, the different hats hung during each life stage drove him to this opportunity he never thought attainable for him.

Cowboy Hat

It all started with a cowboy hat, part of the getup he wore alongside his younger brother as they chased their father through pastures near Santa Rosa, New Mexico.

As a ranch hand and eventually manager, his father tended cattle and settled his family on the ranches where he worked. He and his wife immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico in 1989 in pursuit of this better life for their sons.

Jovani barely remembers the move, but the ranch he spent the next 13 years on became the highlight of his childhood since everyday was bring-your-kid-to-work day.

“There was no watching him from afar,” Jovani laughed. “We were with him if we weren’t in school. If we wanted to get up and watch Saturday morning cartoons, we had to do it at 5 a.m., because by 7 we were out the door doing chores with him.”

This could mean the brothers were on horseback working cattle or bottle-feeding lambs twice a day. They stood by their father as he tended to sick livestock and eventually learned the methods themselves.

Providing medical care for animals got Jovani thinking – maybe, one day, he could do that for a living.

“But it was really kind of a far-fetched idea,” he recalled. “You know, my parents never went to college. No one in my family had.”

It wasn’t until Jovani was in the latter years of high school that he realized he could make college a reality if he wanted. However, he knew he wasn’t ready for such a commitment – neither personally nor financially.

Once he graduated in 2003, he decided to push his aspirations for a higher education to the forefront and enlist in the Army. By November, he was in basic training.

Army Helmet

As is customary in the military, Jovani was able to select a job for which he qualified. In his case, an open position as a medic perfectly aligned with his health care interests.

“The military has tons of experience training people how to do a job,” Jovani explained. “They’re very good at that, so I took to it well.”

By January 2005, Jovani had to put his learned skills to the test during a 12-month deployment to Iraq. He was 19 years old and entrusted with the well-being of his comrades in a mechanized infantry company – whether it be from common cold symptoms to combat injuries.

Looking back, he considers it rewarding that he was able to help his fellow soldiers as the first line of treatment, giving patients his full scope of care before sending them on to a better-equipped medical facility if needed. There was no time for this sort of reflection back then, as he remained focused on critical duties – eyes wide open to the fragility of life.

“I had an aid bag and the health of anywhere from 30 to 40 soldiers in my hands,” he shared. “That’s a lot of responsibility for a 19-year-old kid. It certainly changed my viewpoint on certain things and made me more appreciative than I would’ve been otherwise.”

By the time Jovani returned to the U.S. with his newfound perspective, he wasted no time marrying his girlfriend, Lora, in February 2007. But that meant he had much more on the line two weeks later, when he was deployed to Iraq again.

He served as a sergeant this time – no longer at the bottom of the totem pole – but in charge of soldiers. This meant he felt even more weight on his shoulders but was relieved the military helped him grow and adapt to the challenge.

Jovani served in the battalion aid station, so the combat medics serving as he did before brought the injured or deceased to his makeshift clinic. His interest in medicine was piqued during these critical operations, but when the caregiving subsided, he remained unsure how he would pursue a related field once he returned stateside.

Then one day, while taking inventory in the medical supply warehouse, he met an army veterinarian. They began to discuss the career, and the perks Jovani heard left him with more to consider when he thought about returning home.

Could he make a difference for ranchers in the area like his father by tending to the needs of their cattle and horses? Could he meet a need for food production animal veterinarians in that region?

The possibility of filling such a void left him eager to learn more.

“Visiting with him sparked the idea that becoming a veterinarian would be doable,” Jovani remembered. “I could make it happen.”

By April 2008, he was back in New Mexico and threw the energy he once spent caring for soldiers into chasing his newfound ambitions: tending to the needs of animals and their owners.

Doctoral Tam

The hat worn by graduates earning their Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) is known as a doctoral tam, made of velvet with eight sides – double that of a bachelor’s degree graduation cap.

Jovani knew the extra edges would be felt in his pursuit to wear such a hat, but the challenge did not deter him.

He enrolled in New Mexico State University by that fall semester, majoring in animal science to meet the prerequisite requirements for veterinary school. He was glad to be enrolled alongside his brother, a fellow first-generation student, and that Lora was able to find a teaching job in Las Cruces.

Aside from those perks, he admits returning to civilian life was far from easy.

“That’s definitely an adjustment that needs to be made,” he noted. “That doesn’t happen overnight, and it can take years.”

Jovani found it helpful to channel the self-discipline he formed while in the military into showing up for class and completing his work on time. He was on track to graduate early thanks to dual-credit courses taken in high school and some credits he earned while in the military.

But during his last semester, an organic chemistry course blew his straight sail off course. He passed the class, but not by much.

Jovani felt discouraged not only by the grade, but that he had already spent nearly five years in the military, two and a half in college and was looking at four more years of school.

“That’s seven and a half years of what I viewed as being an institution, and the thought of four more years just really wasn’t that appealing anymore,” he disclosed. “I really just wanted to get out into the workforce and start my life.”

Jovani graduated with honors and then eased shut the door to his veterinarian aspirations to spend the next 10 years working agriculture-related jobs such as with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

A lot of life happened within this decade. Jovani and Lora became parents to a daughter named Adela. They even lived abroad in Russia for a stint as part of his three-year beef production consulting contract – but that opportunity ended with a pregnancy complication.

Lora was set to give birth to twin girls, but they came three months early. Isabela and Micaela barely weighed a couple of pounds, faced special needs and a challenging road ahead – especially when Isabela caught a virus at two months old.

While an adult could have shaken the symptoms, the toll was too much for a premature baby to bear.

“Losing a child is not easy,” Jovani said, voice soft. “I was out of work. We spent those three months in the NICU – three months that I was not working. We depleted all of our savings and leaned a lot on family.”

Hardship can appear as a mirror sometimes, forcing reflection upon life’s most important priorities. During this trial, Jovani and Lora abandoned their overseas adventures and settled back in New Mexico to resume his agriculture career.

With time, in 2016, they moved to a small farm in Lora’s hometown of House – a village with a population of 55. She joked that the closest McDonald’s is more than an hour away.

Jovani’s responsibilities added up as they gained sheep, chickens, cattle and other animals, but he relished caregiving amid the open space. He had long dismissed the idea of ever returning to college as he refused to uproot his family from their home.

That’s not to say there was no regret in the back of his mind, as his veterinarian aspirations frequently stared him down.

“I always found myself working alongside a veterinarian in one way or another,” he said. “If you’re involved in any sort of animal agriculture, you’ve got to have a working relationship with a veterinarian, and I did. I still admired the profession, and it was always kind of a regret that I had not pursued that.”

Then, around 2018, one of those veterinarians shared a whisper about the formation of Texas Tech’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

The prospect seemed promising with the proximity of Amarillo to House versus his other considered option, Colorado State University. He further learned the school shared his intended purpose: to serve rural and regional communities.

These traits slowly drew Jovani back to the door to become a veterinarian – and turns out, it never fully closed.

Jovani and Lora had many discussions trying to nail down the logistics of a two-hour commute, Micaela’s medical needs, the financial risks they would have to take and completing his prerequisite courses.

“It was not a decision we made lightly,” he confessed. “At the time, I had a pretty good stable, long-term job working for the USDA. I was doing really well there, and so walking away from that to start all over would be tough.”

The more they weighed the risks of his dream, Lora admired the light illuminating from within Jovani as he envisioned the possibilities.

Proceeding forward would mean not having her partner’s help on the farm. It would mean juggling her full-time teaching job with her duties as the sole parent of the household on weekdays, leaning on the support of their family and community to fill in the gaps.

Even so, Lora trusted Jovani’s judgment and stood behind him as they braved a step forward in faith.

“It just felt like God put everything right in our path so that we could pursue that,” Lora said. “It was so, so amazing.”

Along the way, they kept passing signs confirming they were heading in the right direction, such as when Jovani improved his letter grade in organic chemistry (to his relief). Then, when he was working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic and received the School of Veterinary Medicine acceptance call he had anxiously awaited for weeks – checking his email inbox at least five times a day following his interview.

But the biggest miracle of all came during orientation, when Jovani discovered he was the recipient of the John and Maggie Windham School of Veterinary Medicine Scholarship Endowment.

This was not just any financial aid he applied for. It was a full ride to attend the School of Veterinary Medicine, alleviating the barrier of affording tuition through one income and student loans.

“It felt like it was even more obvious this was God’s plan for him,” Lora recounted, thankful to gain more allies backing Jovani.

She believes that support will be paid forward as Jovani aims to make an impression far beyond their family.

“When he is a veterinarian, it affects our whole community that’s in desperate need of veterinary medicine to be available to them,” Lora remarked. “It’s like his dream belongs to everybody because at the end of the day, they all check in to help make sure it happens. And like waves upon waves, the impact just keeps going on and on.”

Their support system strengthened through Texas Tech, Jovani moved to an RV park three miles from the Amarillo campus before the fall semester began in August 2021. He has remained there ever since – taking classes during the weekdays, packing up on Fridays and driving home for the weekends.

He has the commute down to an art, leaving at 4 a.m. Monday mornings to account for losing an hour once he crosses the state line into Texas. But the most challenging part of this new venture for Jovani, aside from missing his family, was returning to a classroom setting for the first time in 10 years.

“There was a whole lot of adjusting I had to do to figure out what works for me,” he admitted. “What worked for me studying 10 years ago in undergrad was not going to cut it in this program.”

Thankfully, the best part of joining the inaugural graduating class of the School of Veterinary Medicine is how tight knit the students became, often referred to as “pioneers” as they pave the way for generations of classes to come. Many of these peers were not just study partners Jovani could lean on, but true friends.

Equally helpful were faculty and staff who became his mentors.

“There’s been tons of support along the way, and it’s certainly something I appreciate,” he said. “Everyone wants to see you succeed – they’re rooting for you and are actively setting you up for success. And I don’t think that's unique to me.”

The School of Veterinary Medicine’s practice partners joined the ranks of those investing in Jovani’s future once he began his clinical year last May. His schedule became a lot less uncertain as he traveled to veterinary clinics across Texas and New Mexico – even Australia – sometimes getting to spend the night with his family, other times not seeing them for three- to four-week stretches.

However, this transition from a classroom setting into a professional environment proved exhilarating to Jovani as he put his newly learned animal health care skills to use. His rotations ranged from equine-focused to small animals to dairies – and unlike most other students – he had no prior shadowing, externship or veterinarian technician experience.

Still, Jovani excelled at each turn as the School of Veterinary Medicine Associate Dean and Professor Dr. Britt Conklin observed with pride.

“As a nontraditional student having lived life in other areas, the clarity of his goals is often brought into focus much faster than others who are still trying to fully determine where they want to end up and what they want to do,” Conklin commended. “Jovani has had diverse life experiences that make him comfortable in many different practice and people settings. He also is able to carry himself in a confident manner that projects competency in his medical abilities. These are critical components to a fully mature professional, and this is what has helped him be a success in the clinical year.”

Each different exposure increased Jovani’s confidence, particularly working with cattle and horses like he did during his four weeks on the iconic 6666 Ranch. The more she learned about his rotations, the clearer it became evident to Lora that her husband had found his stride.

“Texas Tech values Jovani’s ability to get things done,” she said. “They value character and work ethic and the actual doing of life, as opposed to maybe just academics. This fits Jovani’s personality perfectly.”

Day by day, Jovani pushed through tasks like basic wellness exams, vaccine visits and specialized surgeries, nearing what he and Lora call the light at the end of the tunnel: his graduation in May. The black doctoral tam upon his head will signify years of sacrifice and determination in pursuit of a title he never thought would lead his name.

Sitting in the crowd during the ceremony, eyes surely welled, will be the ones who never doubted him: his parents, who uprooted their lives so he could pursue such an occupation one day, along with his wife and daughters, who stepped up when he stepped out without complaint.

Standing beside him will be the faculty and peers who encouraged him through both the most grueling and rewarding phase of his life.

“Oh, it’ll be awesome,” Jovani said, voice brimming with excitement. “It will be great to reach that point where I made it – I can practice the medicine I’ve spent four years learning about and can move onto the next chapter in my life.”

Wool Cap

Jovani’s clinical year not only gave him a glimpse of what he could do, but what his career will be like once he moves from his RV park back to House.

He will at long last be reunited with his family but is prepared to be on call and face many late nights. He has actually considered forming a mobile practice to meet this demand for large animal services in his area.

Lora will gladly endure these periodic interruptions to enter their second decade of marriage reunited by Jovani’s side, swapping phone calls in lieu of the warmth and comfort felt around the dinner table – laughing about the chronicles of their day, then clearing the dishes to help their girls with homework.

“What I’m looking forward to the most is getting back into the very heart of all of his adventures,” she said, smile beaming. “He’s not the kind of person that likes to leave others behind. He wants us to come along and see what he’s doing – to actually go and see a clinic he’s working at or an animal he’s treated. That way our family can be more immersed in his goals, projects and dreams again.”

Jovani’s oldest daughter, Adela, is following him a little closer than before these days. An animal lover at heart, she absorbed her father’s tales of veterinary school. Through questions like, “Did you get to do anything cool on this rotation?” she pushed for more details than most, imagining herself in his seat one day.

Furthermore, Adela researched the occupation and watched every veterinarian TV show she could find during Jovani’s absence. With his return, he will undoubtedly be cast as her role model as he switches to the other side of bring-your-kid-to-work day.

“She’s really interested and wants to know more about what I do,” he said. “It’s really neat to be able to share that with her and have that in common with your kid, especially the older she gets.”

Just as he leads his family, Lora believes Jovani has always been meant to be a general of sorts – with an army of community members, colleagues and friends beside him.

Forged with discipline and compassion, he has positioned himself on this front line from the series of hats he has worn – his latest encompassing them all.

When Jovani transforms into Dr. Armendariz, his wool cap could be pulled down anytime, in any weather, to provide veterinary care critical to his community and beyond. No matter what elements or situations he faces, he’ll give it all he has to not hang this hat up anytime soon.

“Looking back, I’d say God has had plans for my family and me for a long time,” he resolved. “We kind of took a long, detoured route to get there, but I’m sure that was all by design.

“I know there’s tons of people out there like myself, later in life, who may have some goals and dreams that they may think are too late to chase. I would say to them, it’s never too late. If you really want it, don’t be afraid. Figure out a way to jump on these opportunities when they present themselves and make it happen.”